The following Private Briefing with Bill Bonner is one of four Bill does each year exclusively for BPR members. This autumn we discuss whether inflation will ever return to normal, the best places to retire in America, whether the upcoming election will be the last in American history, and what books about economics to share with your children and grandchildren

The transcript of the briefing has been lightly edited. If you’re in the United States and interested in the wine Bill and Dan spoke about, you can find more details here.

Dan Denning: Hello everybody. Welcome back to Bonner Private Research. I'm Dan Denning here in Laramie, back in the US after a trip to visit Bill Bonner, our founder over in Dublin, and Tom Dyson, our investment director who flew over from London. But today, I'm joined by Bill from Baltimore. Bill, welcome back.

Bill Bonner: Thank you, Dan. And I see you're back on the plains of Laramie.

Dan Denning: Yes I am. I'm getting ready for winter, but the weather is actually really nice. We get about 30 days of fall, which is after about 60 days of summer, so I'm enjoying it.

But for new readers to Bonner Private Research, this is something Bill's been doing for, gosh, at least five years now. He does a quarterly Private Briefing for our readership where we just take a little bit deeper dive on some of the investment, economic, and sometimes political issues that Bill discusses every day.

This time, I asked you ahead of time for a lot of your own questions, so I'm going to get to those. Thanks to everyone who sent those in because we had some really interesting questions for Bill, which I hope to pin him down on.

But Bill, I want to start with an important question about the Primary Trend, which is a term you've been using to describe the direction of interest rates in the US. And Investment Director Tom Dyson noted last week that something strange has happened in the last month since the Fed cut interest rates, that rather than moving down, interest rates on US government bonds have moved up. And in fact, I think on every single government security, except for the two year and the five year, the yield is now over 4%.

So the question in here is whether the Fed has lost control of interest rates and whether the bond vigilantes are back. And more importantly, there seems to be a conflict between the Primary Trend of interest rates going up, which is our position, and the need for the government to keep interest rates low because the debt is so high. So are those two things in conflict? And maybe who's really in control of interest rates here? Is it the market or is it the Central Bank?

CLICK ON THE IMAGE BELOW TO WATCH THIS PRIVATE BRIEING

Bill Bonner: Well, the subject has driven a lot of people crazy over the years because the interest rates move in funny ways. But the basic idea, the government sets very, very short term rates. So it influences rates more at the short end than at the long end. So what happens is when it does what it's doing now, which is to lower the rates on the short end and to announce a program of lowering rates on the short end.

That's the money it loans to its member banks. What happens is that the investors in the real economy, they see inflation coming. And they then want more money on the long end, where they're lending out money for 30 years to the US government. They think, "Gosh, in 2054, what is that dollar going to be worth?" And we know, from the last 30 years, we know what's happened because the dollar has been more or less cut in half since 1994.

Now we're at the end, we think, of a long trend of lower and lower rates during which the dollar went down. We're at a new stage where inflation is much more obvious. And now, when we say they've lost control, what I think we're really saying is that for the Fed, in order to keep the interest rates from flying off the handle altogether on the long end, as people anticipate more and more inflation, the Fed has to raise rates.

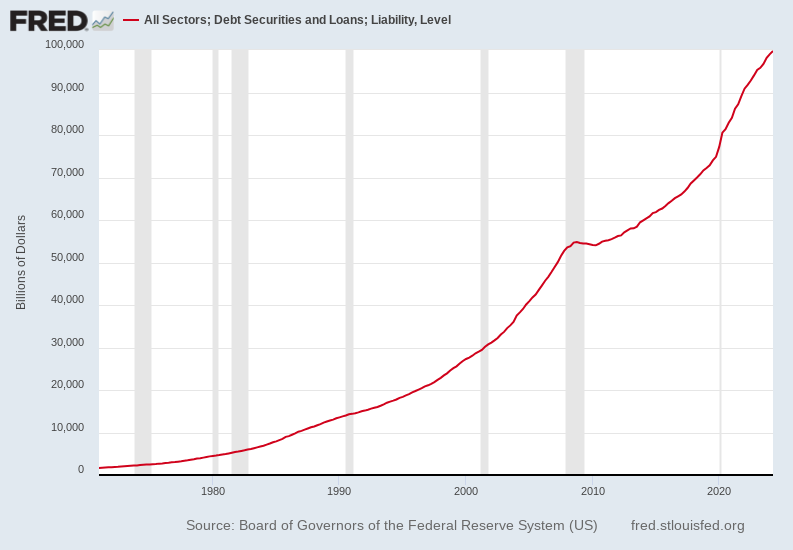

And because they've been having rates so low for so long, there's so much debt, the federal debt at $36 trillion very soon, before the end of the year, and not globally, but nationally, include private debt, financial debt, the debt is over a hundred trillion dollars.

What that means is that if they raise interest rates by 1%, that's a trillion dollars that has to come out of the everyday economy and into yesterday's economy where we bought a pair of tennis shoes on credit.

What happens, losing control of interest rates means that the Fed no longer has the room to raise rates in order to protect the system. And that's what we're talking about, and I think that's largely true. They can try to raise rates a little, but not very much because when they raise rates, as I say, 1% goes to a trillion dollars, a trillion dollars is a lot to take out of an economy, and it's a lot to take out of an economy that already is not doing well. The real growth rate is down around 1%, it's the lowest on average over a period of years, lowest it's been since the Great Depression. It's not a good situation.

I think that's what's going to happen. And when we say the Primary Trend is towards higher interest rates, that's what we're talking about. That the Fed, seeing the need to refinance its debt, needs to put those rates low. But putting the rates lower, from the short term, shows the world that it intends to inflate and shows investors that they better ask for more money when they go and lend money to the Fed or to anybody else. So we're going to see higher rates on the long end, even as the Fed suppresses the day-to-day rates on its Fed funds.

Dan Denning: Yes, I think that's a pretty good summary of it. In fact, we saw today, this is a Thursday when we're recording this and it'll be published on Sunday, but we saw a confirmation that the Fed has also given up the fight against inflation, which continues to be above target. CPI inflation was 2.3%, they expected 2.2%. But the core inflation, which excludes food and energy, was higher than expected. I think it was the highest in 18 months and it was the first increase in, well, it was the first increase in 18 months and it was over 3%. And I saw a statistic today that said, or a quotation that said it's been 43 months since the CPI was below the Fed's target rate.

Investors may need to be prepared for the fact that inflation is now going to be higher than expected. It's never going to return to target, and you've got to adjust your investment expectations and your strategy for that.

But that leads me to my next question. Another way of looking at structural inflation of three to 4% or the cost of living going up regularly is that the quality of life is also going down. So you've got cost of living going up, quality of life going down.

Yesterday, Fortune Magazine published its inaugural list of the 25 best places to retire in America affordably. And you can find this article online, I sent it to you, the number one place was a place I'd never heard of called American Canyon in California, which is about 35 miles northeast of San Francisco. There were other places that you would've heard of, Newport, Rhode Island, Delray Beach, Florida, Virginia Beach, Virginia, Santa Fe. None of these places, by the way, came up on my bolthole list because they were already expensive and much larger than what we were looking for.

But I want to ask you this about in the context of your International Living project, which you started in 1978. And at that time, the idea of retiring overseas was that you could lower your cost of living and increase your quality of life. And whether or not America was a place you wanted to return to periodically or you had kids there, it might be a nice thing to retire overseas.

And since then, you've lived in France, you've lived in the United Kingdom, you've currently live in Ireland and you spend time in Argentina. Do you still think retiring overseas is part of the American dream? Or is it now driven by an economic necessity where the quality of life is going down in America and the cost of living is going up?

Bill Bonner: Well, it's getting harder, I would say that. When we started the International Living Project in, when was that? 1979, places overseas were very cheap. Even places like France, I recall was cheap at the time. And today, is not so cheap. In places that I go, France is not cheap. Ireland, where I live a lot of the year, is not cheap at all. It used to be used be cheap, but it's not cheap.

So it's not that simple anymore, I'd say. And I'd say the same is true with the US, that it's not that simple. I was shocked by those results that you just reported because I do know a couple of those places and have lived down in Delray Beach and in Santa Fe. They're not cheap. They're not cheap places to live. I'm not sure what the criteria for selecting them was, but I don't think cheapness was number one on that list.

And the same is true in the US. In US and overseas, that there are places that are cheap, generally places you don't want to be because what you want is you want a quality of life and the quality of life doesn't come necessarily out of cheapness, it comes out of all kinds of things going on.

And last year, no, it was this year, I went on a trip to Sicily and went into the center of the country. Center of the island actually to a town called Troina. And in Troina, they sell houses for a dollar. Now, that's cheap, dollar house. And they're not bad houses. They need a little fixing up, but they're not bad.

The thing is that the society around them is kind of a collapsing, that people are moving away and that there's nobody there. And you go and you think you're going to enjoy that great Italian experience, that great Sicilian lifestyle, and it isn't there. You have to drive somewhere to get a cup of coffee because the coffee shop is closed up, the restaurants aren't serving or there's one left and it is only open a couple hours a day. So it's gotten to be much more complicated.

Now, in our International Living, which is still going on, we tend to focus on things that are still cheap, but they're very different now. For example, there are people retiring to Mexico, part-time, full-time. And there simply because you can still get things pretty inexpensively. The way they're organized is differently. You're not entering into local culture or local society, you're entering into and expatriate society. You're entering into a retirement community.

Some of those retirement communities on the coast of Mexico are very similar to the retirement communities on the coast of Florida. Sometimes you don't even know the difference. Everybody speaks Spanish in both places, so there's not that much difference. But the ones in Mexico are cheaper and you can live, from what I've seen, you can live quite well down there because it's all set up to be cheap. It's very different from the International Living experience.

So there are those things and there are ways to hedge your bets a bit. Most people, I think, do not go permanently down to Mexico or even to France or Ireland. They go half the year, they have a pied-a-terre. They have some place where they can go if they want to and don't have to stay. That's a whole different thing.

But the answer to your question is yes, there are still a lot of places overseas that are very cheap. We live part of the year in Argentina, less now. But Argentina got to be ridiculously cheap because they had so much inflation. You got a dollar and you could exchange it for like 1,000 pesos. And it really, for time, it was very cheap. It's less cheap today because they're getting their economy together and things are starting to be priced in a more sensible way, but it's still cheap.

And there are things, there are always those kinds of situations and we know people who are moving to places on the other side of the Adriatic and Croatia and even in Turkey where... And Northern Africa for example, and Casablanca, around there, those places tend to be pretty darn cheap compared to what you get in Europe or America.

But coming back to the report on America, what I see is you go to a small town in America and it's pretty inexpensive. You can live very inexpensively. But you won't necessarily find good restaurants and you won't necessarily find that kind of coffee with the cream swirled on top in the shape of a heart. You'll find the coffee comes out of a regular coffee maker. It all depends on the place and the timing and lots of other things.

Dan Denning: It's an interesting question to me because I think it's on a lot of people's minds. When I was in London and Tom and I met with some private investors at Covent Garden, we had a lot of people who were, emotionally anyway, and maybe financially, in this ‘fight or flight’ position saying, "I don't want to leave, but my wealth is under attack and my quality of life is going down. I don't feel safe. It doesn't feel civilized." And it's a big decision to leave all that, whether you're staying domestically or going overseas.

So we'll probably take another look at that next year with The American Bolthole Report. It's been almost six years now since the original report, and it was much different situation. It was pre-COVID and real estate hadn't gone up by 40% in some of these places, so the financial situation has changed.

But I want to follow up on that with you mentioned Argentina and why things are less cheap than they were, that there's a new president who's taken a chainsaw to the size of the government. He's brought in some principles of sound money. He's improved things, by all appearances. So I'm going to ask you later about your plans to go back down there.

But here in this country, there's no Milei on the ballot. We have an election in 26 days. It'll be 23 days by the time people see this. And we are being told by both parties that either this is the most important election in American history and depending on the winner, both sides say it could be the last election in American history, either because one man will dissolve the government and there won't be any more democracy or because there'll be a permanent electoral majority for the left and elections won't matter anymore.

I know these are sensitive subjects in our financial newsletter. But do you think that this election, in your lifetime anyways, is the most important of your lifetime? Or is it as important as people are saying?

Bill Bonner: Well, in one sense, I think it is the most important in the sense that we're getting very near that point where there's no turning back. There's a trigger point. There's a point where the fuse comes and reaches the bomb and it blows up and there's nothing you can do about it. And we may already have been past that point, it's not clear to me. If you factor in politics, it looks like it's already too late.

But theoretically, theoretically today, somebody could step up and say, "Wait a minute, wait a minute, we've gone too far. We got to stop this, we got to balance the budget. We got to bring the troops home. We've got to make put America first," as a real policy, where we spend money that we need to spend and no more, and we get things under control that we stop inflation.

That can be done today. It could be done. Going to Argentina, by the way, they've done it. This guy Milei has proven that even when things are really awful, and they had an inflation rate of 270%, and it was in December of last year, the inflation rate, which they measure week by week because it got to be so high, was running at 11% per week inflation, which is fantastic. And today, the inflation rate is at less than 2% or less than 1% actually per week, which represents a huge, huge drop in the inflation rate. And he did that, that happened. It's real. That's possible.

And he came in and he said, in fact, he gave a speech at the United Nations and at the World Economic Forum, where he said a balanced budget was non-negotiable. He wouldn't accept anything else. Can you imagine a US president today, Kamala Harris saying, "Look, you guys got to give me a balanced budget or I'm not signing it." Or Donald Trump saying something. They don't do that. Nobody takes these problems seriously yet.

What I expect to happen is things to get a lot worse before they get better. And a lot worse, I don't know how worse that is or I don't know what that means exactly. But I know right now, nobody in a major party, in a major position, in a major influence on the country is saying the things that need to be said. And those are that we can't keep spending like this. We can't keep meddling in wars all over the world for no apparent purpose, with no winning strategy. We wouldn't know when we win, they just go on and on and we meddled this one side.

By the way, we are now, the US supported Hamas indirectly by sending money to Israel. Israel gave the money to Hamas. Then we supported Israel to fight Hamas, and then we supported, we do support and have supported the Lebanese army, which now the Israelis, whom we also support, are fighting. It just goes on and on.

In any case, I think somebody, who had some guts and some sense, would say, "Wait, enough of this. We're not going to do this anymore. We're going to go back to being an honest country with an honest economy where people can earn their money and spend it and pursue happiness in their own damn way." That is not where we are and we're not anywhere near, and I suspect things will have to get a lot worse.

In Argentina, it took 70 years, seven decades between the time that Juan Peron announced his new socialism, his Peronism, and the time that Javier Milei came up with the chainsaw and said, "We're cutting this apart." 70 years.

It takes a long time, or as Keynes put it, there's a lot of ruin in a nation. And there's a lot of ruin in America. We have a huge, huge presence, huge colossal footprint, militarily, financially, economically. And I would suspect that there's a lot more downside to come before the upside comes.

Dan Denning: That's kind of what I expected, but I was prepared for that answer because I want to remind you, or more importantly, to remind readers that rather than not having a solution to these problems, one, we think that knowing what's really going on is more important than coming up with a solution.

Being realistic about what you confront is the point of departure for the conversation. But in case people didn't know this, you wrote a whole book about America called The Idea of America, in which you outlined in broad strokes what the solution is to this creeping problem that we have.

So I want to ask you, I'm going to read something to you and then I want to ask you a question. So this is from the foreword to the book, which you published, I think in 2003 with Pierre Lemieux, one of your colleagues over in France.

Bill Bonner: Canada. Canada.

Dan Denning: Oh, in Canada.

Bill Bonner: Yep.

Dan Denning: Okay. So this was in 2003, but you're quoting Rose Wilder Lane in 1936, during the heart of the Great Depression, when really, Roosevelt had brought in a lot of this big government to America for the first time. She said, "Americans today, after the Lincoln administration had annihilated the principle of self-government, but before the Roosevelt team had finished its work," that's you, she said, "Americans today are the most reckless and lawless of peoples. We are also the most imaginative, the most temperamental, the most infinitely varied."

And then you finish this way, this is the introduction to your 2003 book, The Idea of America:

By the end of the 20th century, Americans were required to wear seat belts and they ate low fat yogurt without a gun to their heads. By the beginning of the 21st century, they were submitting to strip searches at airport terminals and demanding higher taxes to protect freedom. The recklessness seems to have been bred out of them, and the variety too. North, south, east, and west, people all wear the same clothes and cherish the same ideas. Liberty has been hollowed out in modern America, but it is still worshiped as though it were a religious relic.

So this is twenty years later. Has anything changed since that? What was the idea of America in your book? And do you think liberty is still a relic that's worshiped or is it real?

Bill Bonner: Well, it's barely even worshiped now, hardly. It's a relic. But it's stuck in some dusty drawer somewhere in a museum that nobody ever looks at. I don't think anybody, I exaggerate just a little bit, but I don't think anybody takes the idea of liberty very seriously anymore as a goal.

They take full employment seriously. They take better healthcare and they got to figure out how they're going to pay the pensions to old people and stuff like that, how they're going to protect against the Russians or... There are a lot of things people take seriously. Or abortion. But liberty is not one of them. Liberty is an abstract idea.

That book, the Idea of America, is a little bit of a play on words in that the point of it was that America is an idea and it's only an idea. It's not a place because America from the time of its founding till today expanded like ten times. It was never the same place, the place always evolved over time. And it didn't matter. If Alaska were no longer a state, there would still be America. And Florida could be cut off California, it wouldn't matter, they're still America.

And it's not a people either. France is French because that's where the French live. But America is not any group of people per se,. It's a group of people who happen to be there and abide by the laws of the United States of America. And it doesn't matter, some are tall, some are short, some are all kinds of people.

It's not a religion. Israel now is a religious state. It's a land of the Jews, of people who are Jews and practicing Judaism. America is not like that. You can practice any religion you want or no religion at all. It doesn't matter. It's only an idea.

And the idea, what's the idea?

Well, the idea is that you're free to do what you want. And that idea has been lost over time because now you have to do what you're told and what you're told is there are, I think at last count, something like 90,000 pages of things that you're told, regulations, instructions and all kinds of things. You can't do business with whomever you please. There are sanctions out on all kinds of things. And you can't make a deal with people. You can't put up a chimney without lining it. There are little things and there are big things. The little things are annoying and the big things are worse.

But liberty is not a value in America anymore, and it's trotted out as a reason to go and kill people. But really, it doesn't really make much sense. So anyway, that was the Idea of America, and I think I ended that book with a phrase of something like the idea of America, well, it was always a good idea and somebody ought to try it.

Dan Denning: I'll have to check on that.

Bill Bonner: Check on the end. I thought that was good.

Dan Denning: Yeah.

Bill Bonner: But anyway, I think that we've evolved way beyond the idea of America. America's a different thing now. It's not even America. It's an empire. We have troops all over the world, 740 bases of American troops who are guarding the world against something, against what? Against anybody who challenges the empire, yes.

Anyway, it's gotten to be a whole different thing. Very expensive, it costs more than a trillion dollars a year to maintain the empire. That's got nothing to do with security. Keeping the security of the US is a fairly small cost, but keeping troops all over the world so that no sparrow anywhere in the world can fall without setting off a sensor in the Pentagon, that's a big expensive enterprise.

You have to give money to one side, then you give money to the other side, then you join up with the first side and you make war against somebody else. That's an expensive proposition, and that's what we do.

Dan Denning: I think that's right. And I will look at the end of the book, but I think even if it's not, it should be the end of the book. Somebody ought to try it.

So let's move to that level where we've talked about the very big picture. A lot of readers wrote in, and I want to get to some of those questions because I appreciate people take the time to do it. And one interesting thing to me is a lot of people asked about your family, in particular, the wedding of your youngest son recently, and maybe a few more questions on that.

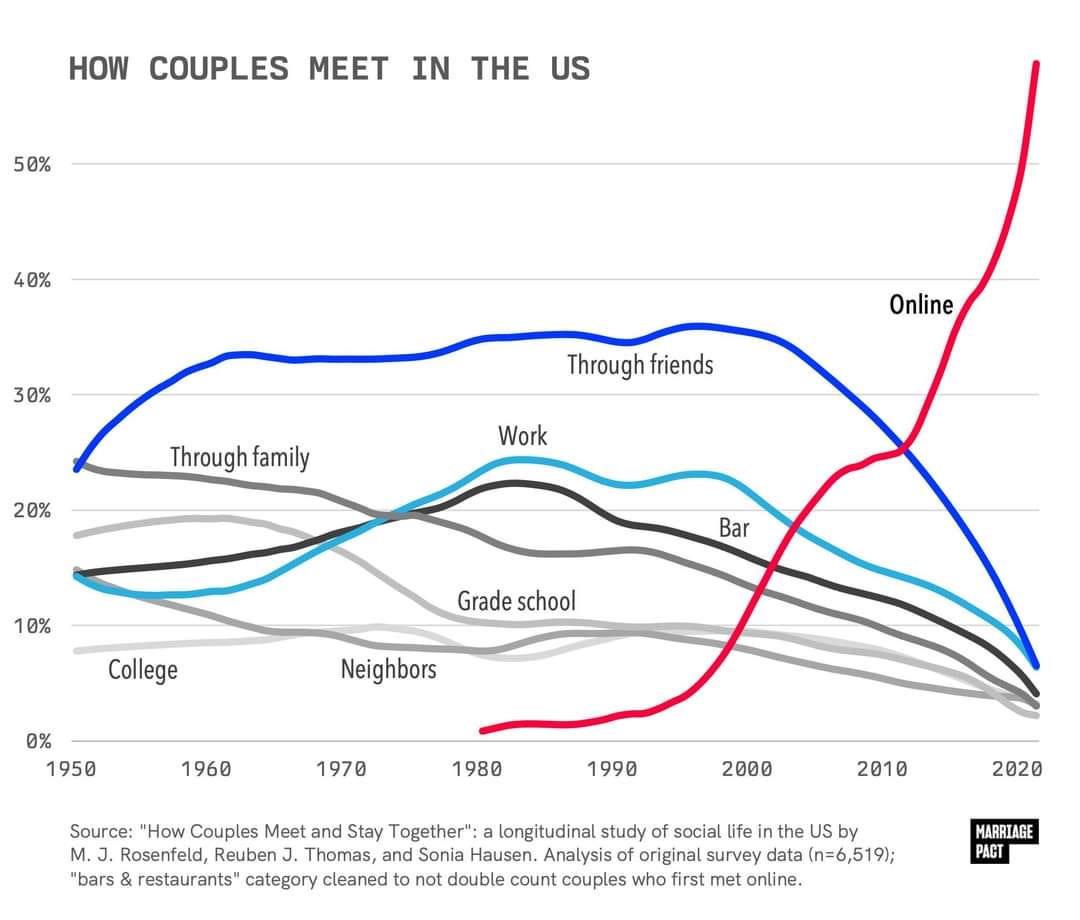

You and I have talked about this before, but America is a very different place today than it was when you were growing up. I saw a study recently that showed that in the 1930s, the way you usually met your future spouse was either they were in the same neighborhood, through a family friend, at church, maybe as a coworker. But starting in 1995, people began to meet their future spouse online. And by now, by 2024, it's by far the most common way people meet their future spouse.

So you've got most of your children married off. What do you see as the role of parents in guiding their children to these big benchmarks in their life? And how was the wedding?

Bill Bonner: Oh, well, the wedding was very, very nice up in Vermont and it was very pretty. Everybody was very nice. It went very well. And the couple were really charming to see. They were seen perfect for each other, which was what a parent wants.

But the larger question's which way the social norms in America are going are hard to understand. But I'd say that one trend is people got together in church, they got together in school, they got together online. And I'd say the latest trend is they don't get together at all because there's a lot of, I don't know what it is and nobody knows why it is, but there's a reluctance to get married and certainly a reluctance to have children.

And the native replacement level, the rate at which native born Americans have children has fallen to such an extent that we do not replace ourselves. That typical woman has fewer than two children, so it doesn't work. America continues to expand only because of immigration, the very thing that our politicians want to shut off. And that's a whole nother discussion.

But I do see that, what looks to me, having been born in the 1940s, that the trends today towards these more casual relationships, less concentration or focus on family, I think is not a particularly good one because when you get old, you kind of need the family. And I don't want to be put in some state mental facility. I want my family, I want to be a burden on my family, so I have to have a family to be a burden on. And if you don't have a family, then who are you burdened on? You got to be burdened on the people who you're not even related to, and they're likely to think, "Well, why do we want to do that? We don't have enough money for ourselves."

I think though these trends that we've been tracking now for many decades are turning in unexpected and not very nice ways because the country owes a hundred trillion dollars. And yet also, the country's getting old. So it is already deep in the hole. But now it must support all these old people too, at the very time when their own families are becoming smaller and less able to support them. Because the younger generation doesn't, for the first time in history, the new generation does not expect to earn as much as the old one.

Now, these are trends which I think almost all can be traced to the money system. You have solid money, a lot of these things don't happen. You can't have a hundred trillion in debt when you have real money because real money, you can't lend out a hundred trillion until you've earned a hundred trillion. And if you've earned the hundred trillion, then you have the resources to lend it out, then you're not poor. But now we are poor because we owe a lot of money and don't really have the economy big enough to sustain that kind of debt.

So we have to sustain, somehow pay off, sustain, wipe out, inflate away a debt of a hundred trillion dollars, and at the same time, support a population that is getting older fast. These people, including myself, we're getting old by the day.

And by the day, our knees give out, our shoulders need to be replaced, you need to find in-home care, that's all expensive too. Where does that money come from when we already owe so much? I don't know where this goes, but I just see that it becomes a huge problem. And when, at first, you deceive with false money, it comes back and haunts you.

Dan Denning: Well, that leads me to my next question because it's a question about what young people should be learning about money and the economy. As I think you quite correctly pointed out, that even though these look like social problems or demographic trends or generational trends, part of it is that when you debase the money, future generations simply can't afford to start families. The cost of services, the cost of education, the cost of housing all goes up.

So on the one hand, for people who already own financial assets, there's this great inflation in the paper value of their wealth. But their children and grandchildren are no longer able to get on the property ladder or they can't afford to seemingly start a relationship and raise a family on a middle class wage. So the middle class has been squeezed because of unsound money.

That's a kind of abstract concept for people. I think people understand it intuitively because it's what’s actually happening. But in a more concrete sense, here's a question from another reader.

They wite, "I have a grandson at the LCE for his junior year," that's in London, College of Economics, I guess. "Do you have any suggestions to ensure that he gets the most from his studies?" What should young people or students be reading about money and the economy to understand what's going on, other than your daily essay?

Bill Bonner: Yeah, my essays trying to touch on everything. But the classics are the ones you want to study. And they mostly come from the old school economists, the Austrians, von Mises and Hayek. And then even before that was the French guy whose name I don't recall right now. But he-

Dan Denning: Bastiat.

Bill Bonner: Bastiat. Yeah, Bastiat really wrote a lot that we don't tend to look at very much because he was French. But he was really right there at the beginning of the understanding about how money actually worked. So I would recommend him very highly, along with the other names, Adam Smith and all those guys, Adam Ferguson. Very, very smart people writing about money.

I think that when economics turned to modern economics, to Keynesianism, then it all got kind of fuzzy and foolish and people began to think things that really weren't true. And today, if you asked, oh, I just wrote about this guy writing for the New York Times or something saying, "Oh, the economy must have more money in order to function, we must have more credit. Naturally, debt rises, so we have to think about what we can do with debt." Of course, he was going on to proposing various jubilees and debt forgiveness and plans like that.

But it's all nonsense. It's not true, it's not the way it actually works. It's the way it's made to work by falsifying what money is, falsifying what the value of credit is and falsifying the whole economy, so you end up with all these curious, bizarre, outrageous things going on. But to get back to the basics, to really understand it, you have to go back to the people who wrote about the basics. And those were the Austrians, Smith, Ferguson and a whole bunch of other people.

Dan Denning: Yeah, there's a new book out (How to Think About the Economy) which is a sort of primer for Austrian economics, which I'll mention when I publish the transcript, that people are often intimidated by reading a book like Human Action by Mises because it's this massive tome and you don't know where to start.

I think the first book, I read it after I started working for you in 1997, was The Road to Serfdom by Friedrich Hayek, which was a great book. And also The Fatal Conceit, which is also very readable. Economics in One Lesson by Henry Hazlitt is also a very good introduction for people to some of these basic ideas. And when you read those, you'll see that a lot of what passes for economic policy or economic thinking by our political class were just stupid mistakes that were tried 100 years ago. And people have just forgotten how stupid they are.

Bill Bonner: And our leading politicians, the two of them, Democrat and Republican, don't seem to know anything about economics. They'll come up with all these things of price controls and tariffs and all these things that we know don't work. Been tried many times, we know they don't work, and yet they come up with them as if they had never thought of them before. They still won't work.

Dan Denning: Well, and it confirms the point you made earlier that we're going to probably have to learn it the hard way.

Bill Bonner: Some things you just have to learn the hard way.

Dan Denning: Unfortunately. Well, let me get a couple more questions and then I'll let you go. One is more investment-related because that's obviously what Bonner Private Research was set up to do, is to help people avoid the big loss with stock markets at all time highs, as they are right now.

We should acknowledge that the S&P 500 and the Dow made new all-time highs. The price-to-sales ratio on the S&P 500 made a new high, so it's more expensive relative to sales than it was in 2000 or a few years ago in 2021 and also 2007. So there's all these valuation metrics where we know the market is dangerously high, but people still have to do something with their money.

So this was a question from Scott. He said, "Bill, I love how Tom has been hitting this portfolio out of the park. I've been recommending Bonner Private Research to friends and family based on my own personal experience. What is the maximum percent allocation to your total portfolio that you would put in your Trade of the Decade?’ And by the way, I have put this question to Tom (look for an answer in Tom’s Wednesday note).

So I'll let you answer that if you'd like. I also wanted to ask a bigger question related to this, that with the AI stocks and the whole investment in AI that's dominated the market since 2023, there was this idea that information is more important to the economy and more important to the next century than energy, than oil. I know your answer on that, but has anything happened in the last year to make you hedge your bets? Or do you still think energy is the best bet for the next ten years?

Bill Bonner: Well, I don't know what the best bet is. I know energy is necessary. I understand how energy works and how it really is the key ingredient in all human progress.

But information, as far as I can tell, for every bit of useful information that's available to people, there are at least ten bits of non-useful, false, stupid information. And the average person or anybody actually has to sort through all nine to find the one that might be useful. I'm not sure that's a good process.

Information itself, I think is greatly overrated because you could, I put it in one of my books, imagining that you're on Napoleon's retreat from Moscow and it's snowing and the temperatures minus 30 degrees, and the Cossacks are coming around killing you, and somebody says, "Hey, Napoleon, here's the formula for a nuclear bomb."

Now, that information is information that took a long, long time to get. It was very expensive and so on. But it's totally useless. That moment in which Napoleon has to reflect on the value of a nuclear bomb is a wasted moment. It's a cost. It's not a benefit. Any information that's not useful to you at the time, at least in a material sense, is an expense. It's not a benefit, it's not an asset.

So information in general, at large, grosso modo, is not a valuable thing. You have to deal with it, you got to sort it, you got to pile it, You've got to stock it, you got to inventory it, and eventually you got to forget about it because it doesn't help you.

So I'd say I don't believe in information, whereas I do believe in fuel. I believe in energy because energy, you know what it does, you know what it's worth, you know when you need it and you're going to need it because the world works on energy.

Dan Denning: As you were discussing it, I thought about with digitization of images and words, which, to be fair, has been great for us, we wouldn't be able to do this project without a lot of the changes that have happened, in my lifetime anyway. But there's been a massive amount of inflation in the volume of just purely digital content. And unless you exercise some discretion and filter out what's useful and what's just a burden, then it does become the worst part of inflation, that everything gets devalued. So you have to work really hard to find the good stuff.

Bill Bonner: Well, even for us, we've been around a long time, at least I have. And I kind of have a feeling about what's right and what's not... What information is useful and what's not.

I have a grandson who spent some of the summer with me and I saw that he absorbed all information and had no way of knowing which was right and which was wrong. So one moment, he'd talk about extraterrestrials that he knew had landed in New Mexico, and the next time, he talked about what was in the US Constitution. And for him, they were both equally true. He had no way of knowing what was true or not.

And I suspect it's true with that with all young people. They have at them a flood of information, ideas, opinions and so on, and how do they sort them out? When they get to be older, then they get to be a little wiser and they're able to say, "Well, I know that's not right. I know that won't work," or, "I know that's probably not true." But when you're young, it's very hard to make those distinctions.

Dan Denning: Yeah, that's a great point. It's more stimulation than information at that point, and it gets people in an emotional state, which isn't always helpful.

Bill Bonner: Yeah.

Dan Denning: One last question for you Bill, and this is related to where we're going to see you next year, but also what you're going to be writing about. So you write about a lot of serious things and some of them polarize people, which I think is the nature of what we do, that you put a view out there and you put some facts out there and people are going to react to it differently.

One of the readers asks, "Does Bill have plans to write more funny, off-topic articles about his personal doings than he currently does?" And that led me to a follow-up question. What is going on with the war with the Originarios at the ranch? And can we expect to hear from you next year at the ranch?

Bill Bonner: Yes, I'm going to be down there in March and April, I think. And surely, the war goes on. I'm not there, my son-in-law has taken charge of it. He, being very young, he has decided that he wanted to make friends with the Originarios. That if he just treated them right, they would treat him right. So far, he's been treating them right, but I haven't seen any evidence that they're going to cooperate.

Anyway, I encourage him to try whatever he can, but people get funny ideas and it's very hard to dislodge those ideas, even if they don't really make any sense for them or anybody else. And that's been the problem down there, that if we were to say, "Okay, you guys, you're right, you take it" it'd be a disaster.

They don't have the knowledge, skills, and capital to manage the project. And where they have been allowed to do what they wanted to do, they've gotten to be very backward and poor. Because they live on welfare payments. It's not a good situation, really. You need somebody who comes in with a big tractor to do something. You need investment really, irrigation.

So the war goes on. I think right now, there's kind of a truce. I think my son-in-law has done a good job of talking to them, and we haven't sustained any damage in the last few months that I know about.

Dan Denning: Well, that's good news to hear. And two things to follow up on that, for readers who may be new to this conversation and have no idea what we're talking about, go to the Research Report section of our website and download a copy of The Lockdown Diaries, which are a series of essays Bill wrote from his ranch in Argentina during the pandemic. And you'll get a taste for the conflict we're talking about and also for what life on the ranch is like.

Second thing is this is my wine rack from here in Laramie. It's a set of elk antlers. It's currently empty, but it will be full in a few days because I have just ordered my dozen bottles of Tacana from Will and the boys at Bonner Private Wines. I sent out a note earlier in the week that said they're selling the last of this recent vintage, and I think there were less than, 1,000 bottles left when they wrote me.

There's less now because I'm going to fill that up. But I'm hoping that next year, I can join you at the ranch and have a bottle of wine with you and talk-

Bill Bonner: Yeah, I'm planning on you coming for a visit while I'm there.

Dan Denning: Okay.

Bill Bonner: Tom was down there this year. I think he had a very good time.

Dan Denning: He loved it and he recommended it highly, so I'll just have to get myself organized and get down there. But until then, I want to thank you again for joining us, Bill, and we'll talk to you soon.

Bill Bonner: Well, thank you, Dan, and until next time.

As usual you slammed israel and tokd 1/2 truths at best. The Lebanese army has moved south but has not engaged the IDF. Israel is a Jewish state but there is freedom for all religions including the two million moslems, the Druz and the Christiana. You have lived too long in Ireland which is antisemitic.

Thank you Mr Bonner, a paragraph with honest prospect and root cause analysis:

What I expect to happen is things to get a lot worse before they get better. And a lot worse, I don't know how worse that is or I don't know what that means exactly. But I know right now, nobody in a major party, in a major position, in a major influence on the country is saying the things that need to be said. And those are that we can't keep spending like this. We can't keep meddling in wars all over the world for no apparent purpose, with no winning strategy. We wouldn't know when we win, they just go on and on and we meddled this one side.

Mr Denning, I concur with you on this, “That's kind of what I expected, but I was prepared for that answer because I want to remind you, or more importantly, to remind readers that rather than not having a solution to these problems, one, we think that knowing what's really going on is more important than coming up with a solution.

Regards,

Mark

P.S.

Little by little, a little becomes a lot: A Tanzanian proverb that highlights the power of small actions and process goals. The quote, “If you take care of the small things, the big things take care of themselves,” is attributed to Emily Dickinson.