The Hollow Class

Sunday, November 9th, 2025

Laramie, Wyoming

Nearly 75% of US households cannot afford a median priced home in America, according to the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB). That’s with a median house price of around $460,000 and a 30-year fixed mortgage at between 6% and 6.5%. Almost a third of renters spend about 30% of their income on rent (Redfin reports that it’s closer to 40% for home owners with a mortgage on a median priced home).

Housing has never been more expense or unaffordable in America. You can thank the intervention of the Federal government (especially the Federal Reserve) for that. Joe Withrow, our old friend and research partner (and architect of the first and second version of Bill Bonner’s Doom Index) has the full story in the essay below. It couldn’t be more timely.

Since I published my weekly research note yesterday, we learned the Trump administration is advocating the introduction of 50-year mortgages in the US. Federal Housing Finance Agency Director Bill Pulte made the announcement on Saturday. Trump posted something on social media comparing himself to FDR, who introduced the 30-year mortgage.

A 50-year mortgage doesn’t make housing cheaper. But by stretching the repayment period over time, it DOES lower the monthly payment on your principal. That lowers the percentage of your total income you’re spending on repayment. And in a strange way, it makes sense.

With a fixed rate mortgage and inflation running in the high upper digits, the real value you of your total debt goes down over time (inflation pays off your loan, as long as your income rises faster in nominal terms). Of course you pay off a lot more interest over 50 years than 30 years. And it takes a lot longer to build up equity (assuming also that house prices don’t fall).

But the point is…the government now knows to keep the housing market functioning and prevent a mean reversion in house prices, more intervention is required. By the way, Pulte also said Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (two firms Joe mentions below) are thinking of investing in tech firms. Why?

Asset prices of any sort—stocks and houses—must not be allowed to crash. Especially before next year’s mid-term elections. The economic and social consequences of a crash are too dire to imagine. What happens next and what should you do?

Quite a bit to think about for a Sunday. The hollowing out of the American middle class has been thorough. But there is an investment side of the story too. I’ll leave the rest of the story with Joe.

Until next week,

Dan

The Untold Story from the 2008 Financial Crisis

by Joe Withrow

It was a humid September morning in 2008 as Daniel Mudd sat in his corner office on Wisconsin Avenue in Washington, DC. He watched the city come to life below him as he sipped his coffee.

Federal motorcades, interns in power suits, and the faint hum of a nation holding its breath all unfolded on the streets below. The greatest financial crisis since the Great Depression was starting to play out.

Mudd had been the chief executive officer (CEO) of the Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA), otherwise known as “Fannie Mae”, for just over three years.

Fannie Mae was created by Congress in 1938 as a government-sponsored enterprise (GSE), but it was a shareholder-owned company with an independent Board of Directors and management team.

Mudd knew that his organization was in the eye of the storm that morning, and he was working through the situation in his head in preparation for an impromptu morning meeting. He had been advised that his presence was needed for an emergency briefing on liquidity with Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, and the director of the newly created Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), James Lockhart III.

At first he thought the meeting would be about solutions. But when Mudd walked into the conference room, he quickly realized it was no such thing... it was a funeral.

Paulson, in his famously steely tone, wasted no time. “Dan, it’s end of the line. We’re moving Fannie into government conservatorship. You need to get your board to consent to this voluntarily and make a nice public statement about it. We already have the press release ready to go.”

Mudd was shocked.

“Hank, we have the capital reserves we need. We have positive book value. Fannie Mae is not insolvent,” he said defiantly.

Paulson nodded but didn’t flinch. “Dan, the markets have lost confidence. We can’t wait. Get your board together to make it official. This isn’t a discussion... the decision has already been made.”

Confidence — not solvency — had become the currency of survival. And Fannie Mae, despite its positive equity and decades of profitability, was suddenly declared unfit to manage itself.

When Mudd returned to his office, aides were already removing nameplates. Apparently word travels fast in Washington.

The next morning, Herb Allison Jr. was announced as the new CEO of Fannie Mae. Mudd couldn’t help but scoff. He knew Allison was a Wall Street veteran with deep government ties. He was there to serve as a crony technocrat who would do whatever he was told.

Most papers called it a “rescue.” Mudd called it what it was: a government takeover.

So that’s it, he thought. His career — and the independence of one of America’s most formative financial institutions — ended with a unilateral dictate.

Mudd swiveled his chair toward the window. Across the Potomac, the Capitol dome gleamed... but for the first time in his life, Mudd felt utterly powerless.

His removal – and Fannie Mae being placed into conservatorship – each came out of the blue. Mudd hadn’t been warned. There hadn’t been a boardroom showdown. There was no Congressional hearing. Not even a discussion.

Instead, an aspiring technocrat working alongside the Treasury Secretary and Federal Reserve Chairman made a far-reaching decision behind closed doors.

Artist’s Rendering of Daniel Mudd’s Corner Office at Fannie Mae Headquarters

As the news broke across the media networks, a new narrative took shape — the one that would persist for years: Fannie Mae and its CEO Daniel Mudd had caused the financial crisis.

That was the spin. It was all Fannie Mae’s fault.

In the hours that followed, reporters camped outside Fannie Mae’s headquarters. Lawmakers filled Sunday talk shows with feigned righteous fury. “Fannie Mae fueled the bubble,” they said. “Fannie Mae bought toxic loans!”

Mudd was painted as the reckless captain who’d run the ship aground. And inside the company, morale collapsed. Fannie’s underwriters, analysts, and administrative team watched their stock-based retirement plans vanish in real time.

It was infuriating... but Mudd knew the real story. It began years earlier, when the seeds of the housing bubble were quietly sown by policies that were never his to control.

Lighting the Fuse

In the early 2000s, after the dot-com crash, the Federal Reserve slashed interest rates to historic lows — first to 2%, then lower. The goal was simple-minded: revive a wounded economy with cheap money.

But cheap money has a way of finding a home, and it found one in housing...

As interest rates fell, investors swarmed into real estate, lured by yields and the illusion that home prices never fell. Wall Street’s private-label securitizers were soon packaging everything from pristine mortgages to what were effectively loans scribbled on napkins, thus turning them into bonds that glowed like gold — until you looked too closely.

For their part, the regulators and ratings agencies conveniently looked away and allowed the bubble to grow. Fannie Mae watched the frenzy from the sidelines at first.

The company’s mandate — written in law — was not to chase profits but to promote affordable housing. That is to say, to make sure that teachers, nurses, and other first-time buyers could own their own homes and unlock the American Dream.

But as Wall Street flooded the market with high-risk mortgage products, political pressure mounted. Congress demanded that Fannie “do its part” for low and moderate-income families.

In fact, regulators told Mudd to buy riskier loans to meet affordable housing goals, while Wall Street’s roaring machine made even the most cautious underwriting look obsolete.

“We were never the spark,” Mudd would later say. “We were the backstop.”

By 2006, the line between acceptable lending and reckless gambling had blurred. Fannie Mae’s charter required it to support homeownership across income levels. But that also meant buying and guaranteeing loans that private banks were walking away from — loans the market demanded but would no longer hold.

When Mudd looked at the company’s balance sheet, he saw both danger and duty. Fannie Mae’s capital position was solid — billions in positive equity — but the ground beneath the housing market was shifting fast. Defaults were creeping upward. Private-label securities were unraveling. And yet, every signal from Washington said keep buying. Keep the market liquid.

Then, in 2007, the exodus began. Private lenders fled. Hedge funds stopped bidding on mortgage-backed securities. The same institutions that had preached the gospel of innovation were now running for the hills.

“We didn’t get to run,” Mudd would later attest. Fannie Mae had a mandate to backstop the mortgage market, and the organization was under intense pressure to do so as the housing bubble reached its apex.

Fannie Mae became the buyer of last resort. It was the sole institution propping up an American dream of homeownership that the market itself had abandoned.

Mudd knew the risks were mounting. But the alternative — letting the housing market freeze — was politically unthinkable. He was under intense pressure from the same policymakers who would later condemn him when the jig was up.

When Fannie Mae entered government conservatorship, it had more than $45 billion in positive assets on its balance sheet. The company wasn’t bankrupt. Instead, it was used as a scapegoat to direct blame away from other power players who were far more instrumental to the housing bubble and its historic bust.

And as we’ll see, Fannie Mae’s conservatorship was used to instrument a massive theft of the commons that left the once-great American middle class broken, hollow, and amenable to political radicalization.

An Instrument of Generational Theft

While it’s certainly true that Fannie played a role in enabling the fraud and frenzy, the reality is that it was only a somewhat unwitting accomplice to the financial crisis of 2008.

The US government placed Fannie Mae into conservatorship on September 6, 2008. At the time, they promised that conservatorship would just be a bridge—an emergency structure to help Fannie navigate a once-in-a-century storm without market pressures.

Various power brokers within the US government repeated that same narrative for years. They emphasized that Fannie’s conservatorship was just a temporary arrangement and that it would end when the organization could get back on its feet to fulfill its mandate.

Well, Fannie Mae returned to profitability in 2012 after three years of net losses that it absorbed with a $116.1 billion capital injection from the US government. From that point forward, the company generated well over $10 billion a year in positive earnings in most years... but the organization was never permitted to exit government conservatorship.

Instead, all of Fannie’s annual profits from 2012 to the present were “swept” into the US Treasury. That means the US government confiscated Fannie’s earnings. The company has not been allowed to use its net income to recapitalize itself.

At first this “net worth sweep” was justified as the means by which Fannie would pay back the money that it received from the government during the financial crisis.

But by the midpoint of this year (2025), the US government had taken $203.8 billion in earnings from Fannie Mae. That means the “sweep” program has taken nearly $88 billion more from Fannie than the organization originally received as an emergency capital injection.

Yet, there’s been an overt effort to keep Fannie in conservatorship. The Corker-Warner bill of 2013 proposed to set the company free after Fannie became profitable again... but that bill was crushed.

After that, the issue went silent for several years until the first Trump administration proposed to privatize Fannie Mae in 2019. But then the Covid hysteria unfolded and nothing ever came of the plan.

So Fannie Mae has been suspended in animation for nearly two decades now.

And while one can make the case that a true free market in housing would not include a government-sponsored entity, the reality is that Fannie Mae has been instrumental to the widespread availability of 30-year fixed-rate mortgages since its inception. That’s because Fannie purchases mortgages from lenders and bundles them into securities while also providing a payment guarantee to investors.

This steady secondary market enables lenders to replenish their capital and confidently offer long-term, fixed-rate loans—like the 30-year mortgage—at stable rates and on a mass scale, regardless of local deposit base or economic volatility.

So while the GSE structure distorts the free market, 30-year fixed-rate mortgages would be rare without Fannie Mae. And in the instances when a lender was willing to do a fixed 30-year mortgage, the borrower would have to be pristine and the interest rate would almost certainly be much higher than what it is today.

That’s not such a bad thing in a market that hasn’t already been warped by the availability of cheap credit. But in an economy that’s been hyper-financialized with inflated home values, making cheap credit accessible to regular people enables some semblance of a middle class to remain.

With that in mind, being stuck in government conservatorship has dramatically limited Fannie’s ability to support first-time home buyers.

Prior to 2008, Fannie Mae’s backstop enabled Americans to obtain conventional mortgages with a down payment of just 5-10%. And this was true prior to the housing bubble as well – before underwriting standards went out the window.

This enabled first-time home buyers who had moderate income and “good-but-not-great” credit to get into starter homes with a little bit of savings.

That all changed after 2008.

With Fannie in conservatorship, lenders tightened standards across the board. And while the rules still allowed for lower down payments, it became virtually impossible to obtain a conventional mortgage for less than 20-25% down.

Now, this alone isn’t evidence of sinister activity. But look at what was happening in parallel...

The Great Middle-Class Heist

On December 16, 2008, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke announced his intention to move to “zero interest rate policy” (ZIRP), and he slashed the federal funds rate to zero that same day.

Of course, Bernanke talked about stimulating the economy and creating a “wealth effect”... and I suspect he actually believed it. But the reality is that the ZIRP policy created a once-in-a-lifetime carry trade in single-family housing.

Up to that point in American history, no financial institution owned a large portfolio of single-family homes. But the ZIRP era invited a mad stampede of institutional capital into the American housing markets because the institutions could borrow at rates near zero to buy homes. Then they could generate a large profit spread by renting those homes out to regular people.

By 2015, large institutional investors like Blackstone, American Homes 4 Rent, Waypoint Homes, Cerberus Capital, and others owned upwards of 300,000 single-family homes in the US. By mid-2022, that number had ballooned up to about 574,000 homes.

In southern cities like Charlotte, Atlanta, Jacksonville, and Tampa, these institutional investors controlled 15–25% of single-family rentals, which changed the entire character of entry-level neighborhoods and the dynamics of the local housing markets.

In total, tens of billions of dollars poured into single-family housing. Estimates suggest that the financial institutions invested between $60 and $100 billion in single-family homes to take advantage of the cheap credit made available by the ZIRP era.

Naturally, this drove housing prices up to artificially high levels. I have a first-hand example to quantify this.

For those who know my story, my first career was in the corporate banking arena. I worked in Charlotte, NC, which is the second largest banking hub on the east coast – second only to Manhattan.

However, I became completely disillusioned and disgusted with the corporate banking world, and I made the decision to walk away from it in 2013. As part of that process, I sold my home in Charlotte and used the proceeds to buy a five-acre property up in the mountains of Virginia.

I considered myself lucky at the time, because my home in Charlotte was on the market for a grand total of three days. We received a cash offer within three days of listing the property, and the buyer didn’t even want to come see it. From a seller’s perspective, nothing could be better.

Well, I found out when the contract came that the buyer was a company called American Homes 4 Rent. I had never heard of them before, and I thought it was a little odd that they wanted to buy my little 3-bedroom, 2-bathroom home in the Charlotte suburbs. But I already had my Virginia mountain property picked out... so I was grateful for their offer.

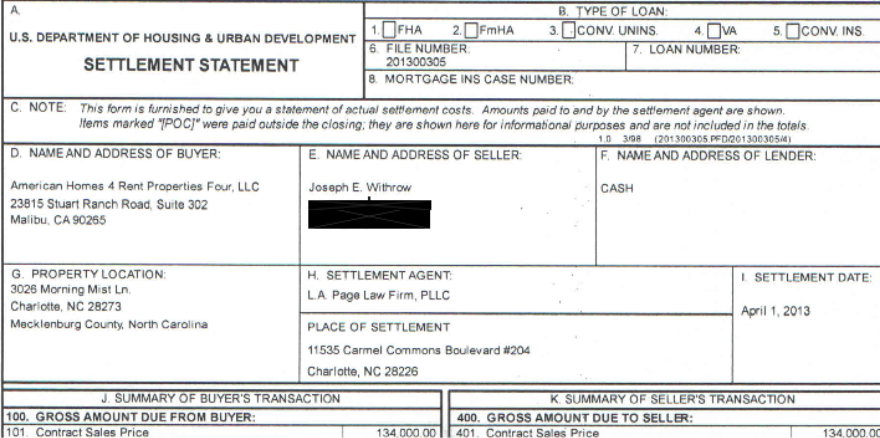

I purchased that home for $110,000 in 2011, and I had paid the mortgage down a fair amount. They offered me $134,000. Here’s the closing document:

If this were just a one-off situation, it wouldn’t mean anything to anyone other than me. But little did we know at the time, institutional investors like this one were buying up hundreds of thousands of properties across America. This drove housing prices up to astronomical levels.

In the case of this home that I was able to purchase for $110,000, it’s now worth around $370,000. That’s a 236% increase over what I bought it for just 14 years ago.

And here’s the thing – I would never have been able to afford this little home in 2011 if it cost then what it does today. I would have been hard-pressed to save enough for a 20% down payment based on what I was earning at that time. And even if a 5%-down option was available to me, I wouldn’t have been able to afford the mortgage payment.

Yet, this is just a 1500-square-foot starter home. There’s nothing luxurious about it.

Now, if we look at the data – median wages in the US have risen by 57% since 2011. That’s not nearly enough to keep up with how much housing prices have increased.

So I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that I doubt any first-time home buyer can afford my little starter home today. They’ve been priced out of the market. That’s probably why American Homes 4 Rent still owns the home to this day.

So let’s connect the dots to reveal the story arc here...

Fannie Mae Placed in Conservatorship: Fannie Mae was taken over by the government in September 2008. Lenders have required that homebuyers put down between 20-25% of the purchase price to buy a home since then.

Earnings Sweep: Fannie Mae has had over $203 billion in net earnings swept away from it since 2012. This has left the company as a perpetual ward of the state rather than a fully recapitalized, counter-cyclical engine for first-time buyers per its original mandate.

ZIRP Empowers the Institutions: The Fed cut interest rates to zero in December 2008 – just three months after Fannie was placed into conservatorship. This made credit available to financial institutions at rates that were far below the rate of inflation.

Wall Street Invades the Housing Market: In the wake of the ZIRP era, a new class of single-family home buyers—armed with cheap capital—rushed into the market.

Financial institutions bought over 574,000 single-family homes across America with the Fed’s cheap credit, which drove prices higher and made it nearly impossible for new first-time home buyers to enter the market.

For a household earning around the median annual income, the difference between scraping together a 5% down payment prior to 2008 and suddenly needing to come up with 20% of a massively inflated home price today is a chasm that can’t be reasonably crossed. Not to mention, mortgage payments at these inflated price levels are absurd.

For young people, what we’re talking about here is a tale of two worlds.

We’re talking about the difference between buying a starter home and settling down in their 20’s – perhaps getting married and starting a family – as was common for young people for much of the past century... or having to face the harsh reality today that they have very little agency in their own life because it’s nearly impossible to get ahead financially – as is the case for so many people in their 20’s and 30’s today.

Is it any wonder why the percentage of home ownership among young people in the US today is historically low? Is it any wonder why the rate of marriages and childbirth are down?

In 1990, about 45% of young adults aged 25-34 in the US were homeowners. By 2024, that percentage had fallen to just 26%.

Meanwhile, nearly 60% of young adults in the US were married in 1990, and the fertility rate was 2.08 children per household. By 2024, less than 39% of young adults were married and the fertility rate had dropped to just 1.62 children per household.

Putting it all together... is it any wonder why so many young people are screaming about capitalism, dying their hair blue, and gathering at Antifa rallies across the country?

We now know that many of these protesters are being paid by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) funded by billionaire globalists to participate in these rallies... so there’s a financial incentive in place.

But still, would this really be happening if the majority of young people in this country were married homeowners who were focused on their careers and raising their children with the prospects of a better future?

What we’ve seen since 2008 is nothing short of a theft of the commons. Except it happened in little pieces that seemed unrelated at the time. But if we look at the story holistically, it all comes together.

When we step back and view the entire picture, what emerges is not just a story of market excesses and economic shifts. What we see is the gutting of middle America – be it intentional or otherwise.

Now the question is – are we going to see the restoration of the American middle class in the coming years... or are we going to watch everything devolve into a modern redux of the War Between the States, more commonly but mistakenly known as the American Civil War?

-Joe Withrow

P.S. This is just the beginning of a Phoenician League special report titled The Modern Theft of the Commons and a Hidden Opportunity. If you would like to read the full report at no cost, you can find it here.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were scapegoated to cover for Chris Dodd and Barney Frank forcing FNMA to buy the worst of the worst mortgages in the name of affordable housing. That Mudd was singled out and none of the real players who perpetuated the housing fraud were put in jail is just one of the travesties of this story of middle class destruction.

Yep, if You want government In Your life , You will pay for this endlessly for all Your time on this earth. The famous words-more or less, I am from the government and I am here to help You.