Tuesday, February 11th, 2025

Boulder, Colorado

by Dan Denning

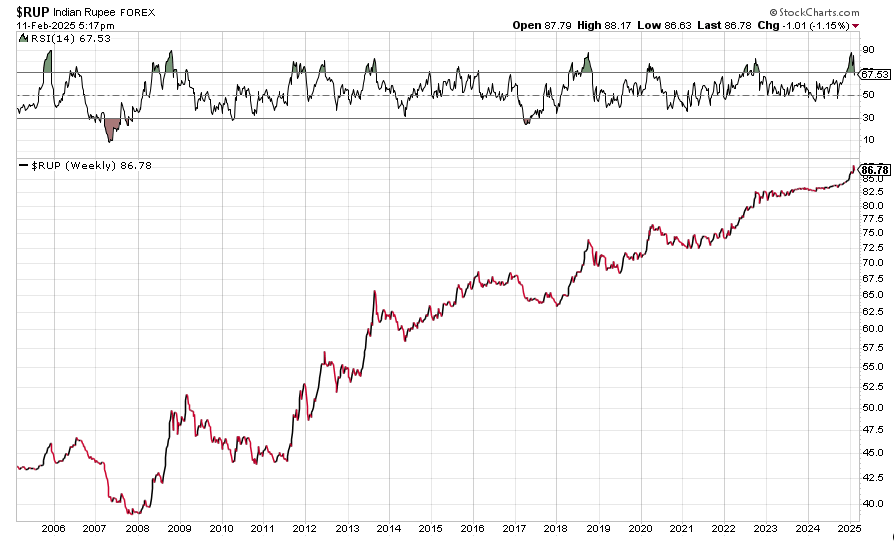

Here’s something I learned last week: India ran a $32 billion trade surplus with the United States in 2023 on $118 billion in two-way trade. President Trump has called India ‘a very big abuser’ of unfair tariffs with the US. And as you can see from the chart above, India’s currency, the rupee, recently made a new multi-year low against the US dollar on speculation that Trump tariffs would hit India hard.

Indian President Narendra Modi arrives in Washington tomorrow to meet with ‘The Donald.’ India is expected to agree on importing more us energy, and possibly weapons, to build on its mutual goals in the region (to thwart China). The rupee reversed its swoon in trading yesterday. Is this a good time for US investors to look at Indian stocks?

Last week I talked with one of Bill’s long-term business partners from India, Ajit Dayal. We had a wide ranging discussion, as you’ll see from the transcript and video below. It’s a slightly longer Private Briefing than normal. But timely as well, given Modi’s impending visit.

Enjoy,

Dan

PS I’m headed back up to Laramie later today. In the meantime, you can learn more about the newly listed fund Ajit and his team have put together by going here. The ticker symbol is QINIX. Please note there is no financial relationship between Quantum and BPR.

TRANSCRIPT BEGINS (lightly edited for clarity)

Dan Denning: Hello, everybody. Welcome back to Bonner Private Research. I'm Dan Denning, and as you might be able to tell, probably not because of my blurred background, but I'm back at the mothership at the wor ld headquarters of Bonner Private Research in Baltimore. Because of the time difference and because we planned it well, it's my privilege today to introduce a longtime business partner of Bill's and one of the premier investment experts from India. He's been at it for over four decades, Ajit Dayal. Ajit, welcome to the show.

Ajit Dayal: Thank you, Dan. Thank you for having me, an honor, my pleasure.

Dan Denning: You're welcome. I'm going to give you a chance to introduce yourself because you're going to do a better job than I would, but I will let our readers know that Ajit has some background in the US. He got his MBA from the University of North Carolina in 1981, and then in 1990 when it was an entirely different world, this is before China was in the World Trade Organization, before a lot of the issues we're dealing with today, he started Quantum Advisors in India.

Just recently, the reason he's talking to us today, we have good news for US investors. They now have access to Indian equities through a fund that's been launched by Ajit and his partners called the. The website is QASL.com and if you want to find more about it, which we'll tell you about in a little bit, click on the India Fund. It's a fund of anywhere between 25 and 40 companies that give institutional and individual investors in the US exposure to what's going on in India.

That's what we want to talk about today because as Bonner Private Research readers know we've been banging the drum about excessive valuations in the US, but from his end, Ajit's been working on how to value companies from the bottom up and do so with integrity. I know that's an important word to you. Let me turn it over to you first and allow yourself to introduce yourself and tell us a little bit about your background and how you started working with Bill Bonner.

CLICK ARROW ON IMAGE BELOW TO PLAY VIDEO

Ajit Dayal: Thank you for that, Dan. I think there are a few things. One is that when I started Quantum in 1990, India was very much the closed economy. We had the Berlin War fall in October '89, and prior to that, India was sort of Soviet Union facing in terms of government policy. After the Berlin War fell, I guess we looked around the world and said, "We have to choose which path we want to move. This was a failed path. Let's move towards sort of Westernized capitalism."

We turned a lot to the western world with our reforms in July 1991 onwards. It's strange because India has been by and large a socialist government running a capitalist economy in the sense that no street, if you go around the streets of India, the people who will shine your shoes and people who come and wash your cars and all that stuff, and they've never done an MBA.

They don't know cash flow, but they know survival. They know that markets can give them a job if they have a skill set and they offer that skill set. Imagine the guy who's polishing your shoes in India, understands cash flow, understands inventory, and understands pricing, right? You had that framework at the level of the people, but you had a government that can't afford, so historical reasons became socialist in terms towards Soviet Union. But I'll talk a bit about how I met Bill.

Around that time in 1990, I also set up a research only website for India now called Equity Master. It's a bit like Value Research in the US where you pay subscriptions and you get independent research, et cetera. It was really designed more for high net worth and retail investors in India want to build their own portfolios.

We had a subscriber from India who actually moved to the US and she came to work with Agora and she sent us an email saying, "You really should meet this guy called Bill Bonner." I flew to DC on one of my various trips to America and I went to meet this guy called Bill Bonner in Baltimore and we hit it off instantly. Bill had just launched that fantastic book of his, which is the Empire of Debt. When I read that book before meeting, I was absolutely amazed at the thought process and his writing style and all the stuff he was doing and had done. I think we just shook hands on a deal in a few minutes, like you know that Agora will pick up a stake in that research arm of ours, which has nothing to do with the investment company. When we started Quantum in 1990, we were all one entity and the regulators in India, SEBI, Securities Exchange Board of India, like the SEC, was born after us.

When the regulator came in, they started having silos. If you manage money, they do this company. If you're doing independent research, do it in that company. We had to split the companies up into different arms, and that's the connection with Bill. Yeah, I've known Bill for many, many years. I don't meet him, sadly, as much as I would like to, but I spoke to him a few weeks ago and said, "We're going to fix that in 2025." He said, "Yes, we will meet more often." But that's how I met Bill going back in history.

I'd just like to run through a bit about what we see in India, what we have been seeing and studying and where we think India is likely to go given our experience of decades of actually looking at India as an investment destination. I'll just share a couple of slides. I love doing slides because I think pictures are worth a thousand words, and much as you and I speak very well and articulate things, images are fantastic.

This is just a map of India for people who haven't seen a map of India, pretty long country south to north. South is very hot and north is very, very cold. That's Kashmir and the Himalayas on the northeast and all those dots are basically places where we have gone to visit and see factories of companies. We don't do desk research, we actually go out and understand what's happening on the field.

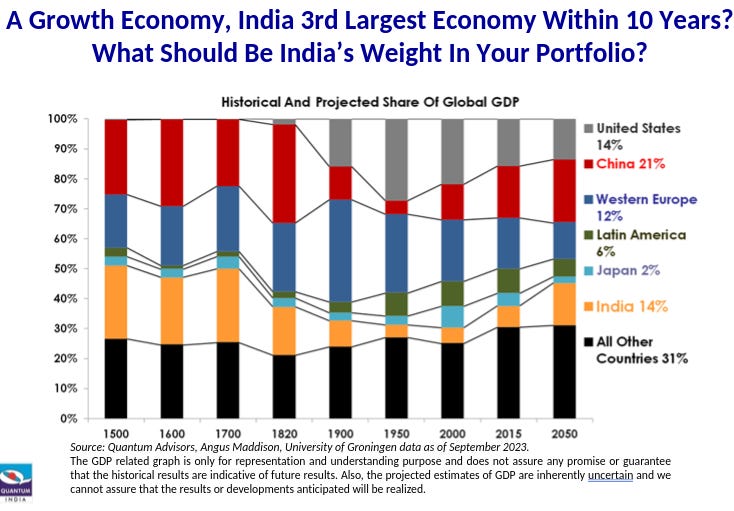

Of course, there are many parts of India where we haven't yet covered the dots, but it's a big country and we have covered a significant part of the geography out there. This was a chart that was done a few years ago by a guy from the University of Groningen, Mr. Angus Maddison, sadly no longer alive. He went back 500 years or so in history to look at the share of different geo-regions of the world in global GDP. Red is China and the yellow orange is India.

You can see how in the 1500, 1600s before the Industrial Revolution, China and India basically had half of the measured global GDP in the world. You talk about the new silk route and the silk route, and that was all part of what constitute global GDP. Then you had the Industrial Revolution that I alluded to, and India and China lost out in the Industrial Revolution.

Then the US is born, as you can see in the 1900 chart, you see the gray on the top. That's United States coming in and becoming a larger part of the global pie. Of course, the world order changed after World War II, and then you US became much more dominant after World War II, and then later on you had China joining the WTO and the red begins to expand. After Mao's massive mishap of the great leap forward, which really was a great jump backward, you had the US-China trade treaties, you had Nixon going to China 1971 July along with Kissinger. You had changes within China. You had China joining the WTO. Within India, you had a similar context as I referred to. You had the fall of the Berlin Wall, you had India looking more westward and more to the US and the OECD and Europe as to what the business model for the country should be.

As you extrapolate that in the future, and these are our estimates going out to 2050, in terms of what the sizes of China and India could be in global GDP, of course, trade wars, tariffs may change some of these moving past. They may not, on a decade point of view, they may not make a difference. But the point being that India and China have arisen and they are a significant part of global GDP growth.

If you look at where India is compared to China, so on many fronts, we are decades in some cases behind China, right? China began its path ahead of India. We began in 1991, and as I indicated, China began to change after Nixon's visit to China in '71 and thereafter when it formally joined the WTO and took a great leap forward. India is decades, in many cases, behind China on multiple fronts. The question to really ask is India getting there or are they going to be massive speed bumps and pitfalls along the way?

Dan Denning: Ajit, can I stop and ask you a question. You mentioned the word and I just wanted to interject and ask a question about it because it's very timely right now that two things really, India is the "I" in BRICS, and of course right now we have the new Trump administration seemingly conducting trade wars via tariffs with key US trading partners, which would be Mexico, Canada, and China. The C in BRICS, from your point of view, in the short term anyway, is India implicated at all in potential tariffs from Trump or is it largely outside that whole regime?

Ajit Dayal: Well, Trump has after he won the election and joined the campaigning called India ‘rogue’ on trade fronts. Again, we're a small part of US trade, but we have a surplus with the US. Our services exports to the US have generated more income for us. Basically President Trump is trying to say, ‘Hey, I need to balance this trade,’ and that's what the tariffs are all about. ‘You better buy more goods from me rather than having all these surpluses and me making you rich in the process.’

Then there was an old saying that I remembered when I went to North Carolina to the University of North Carolina for MBA, which said, "America educates its adversaries." What Trump is also saying is that America's also enriching people who can become its adversaries in that sense, whether it's a Panama Canal or whether it's China, I'm buying your stuffed toys, you become rich and then you go out and you start sort of bludgeoning me in the superpower domain.

To go to your point, India has issues with the US. Pre Trump's nomination and swearing in, we've already begun to reduce tariffs on certain US goods, so therefore, preempting Trump's anger in some sense, trying to calm him down. Our prime minister's arriving in the US on the 12th of February for a couple of days to meet President Trump. Just a few days ago the US government announced that they are sending 18,000 illegal immigrants who've come in from India back on military transport planes to India. Our prime minister is coming with a plane and he probably will take a couple of the illegal immigrants back with him to get some goodwill.

I think there will be some dislocation, but recognize that India's share in global trade is not even one-tenth of that of China's. We're very small in terms of our impact and as an economy, while there are certain sectors and certain industries which do rely on exports, we are very much a domestic driven economy. We don't have the infrastructure that China had to build out supply chains for the multinationals. Right from SARS in 2003, when the multinational keeper altered sources to Covid, India hasn't quite made the cut as yet, but we will talk more about that.

Dan Denning: I'll let you get back to your presentation, but I think that's a really important point to make with respect to the fund that you've set up. Because for the last two decades, American investors who tried to make money in Chinese stocks, and of course the Chinese government through the communist party had a program of fixed asset investment, which had a policy goal, didn't really have anything to do with cash flows for Chinese companies. It was always very hard for American investors to make money from Chinese companies whether they were doing business in China or America.

What I really liked about what you and I talked about before the call was that you're looking at businesses in India, the largest democracy in the world, one of the largest countries in the world that are generating cash flow from their business in India, not through their exports to the United States. There may be companies that do that, but primarily you're just talking about businesses that are growing in an economy that's growing and trying to buy them at a great price. It's really just an investment problem, it's not a policy problem.

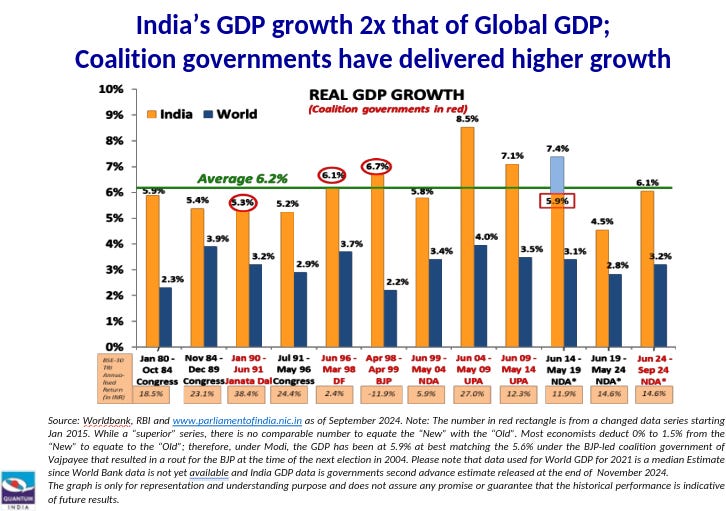

Ajit Dayal: Correct. Yeah, absolutely. We do have stocks in the portfolio IT services they export primarily to the US and Europe and Japan, but those are few and far between. But I'll just talk about the India story a bit at this stage. This series of bar charts goes back to 1980, that's about ten years before I started Quantum. It shows GDP growth rate while each government was involved. That's in India and that's the orange bar and the blue bar shows global world average GDP growth rate. If you just eyeball this over the... We now have the 12th government that was elected in June 2024 on the extreme right, but look at the first 11 bars, you'll see that global GDP has always been lower than India's rate of growth in GDP, irrespective of which government was in power and what the time period was.

This is across all cycles in terms of economic cycles and market cycles. You've had high interest rates, you've had low interest rates by the Fed, you've had a weak dollar, you've had a strong dollar, you've had LTCM collapse, you've had the Asian crisis, you've had SARS, you've had Iraq, Afghanistan, you've had a bunch of things happening in the world including Covid and Lehman. India just kept going at a relatively decent rate of growth and certainly twice the global average. The other interesting part about this, which is completely contrary to what the press indicates, that in India on the X-axis, when we have the letterings of the governments over the years, the black indicates single-party governments and the red lettering indicates coalition governments and the press always tells us, "Oh, India needs a strong government and India needs single-party."

Actually, the data's telling us, if you look at it that whenever you had red coalition governments, the probability of exceeding that long-term average in the green line of 6.2% per annum real rate of growth at GDP over 44 years, the red coalition governments had a better chance of crossing that red line, crossing the green line than you had single-party governments. During single-party governments, you actually grew less than the long-term average. That's something which people don't get. Then we said, "No, there's a reason for it." It may not be scientific reason, but we can tell you that a coalition government is so busy staying in power fighting among themselves to not to disrupt it, to fall as a government, that you leave us alone and you leave us alone.

Remember I spoke about the shoe shine guy on the street who comes to clean your car and clean your shoes and clean your windshield? He doesn't have to worry about stupid government policies, but when you have single-party governments, they have the power and they have the ability to come out with bad policies, then you can just see that when look at the black lines, look at the black lettering and you can just see how most single-party governments and all of them, actually, have had lower rates of growth than the green chart of the 6.2% 44 year average.

Now, of course, we have a coalition government on the extreme right since June 2024, and we're hoping they start behaving like a coalition. So far they are not. Prime Minister Modi in this third term as a coalition government, as a true coalition, is still not functioning as a true coalition. He's still coming up with dictates and what he wants. You never hear the coalition partners talk about economic policy. We're hoping they start behaving like a coalition government so that we can get maybe beyond that 6.2% rate of long-term. We believe that 6.2% will continue, but we'd love to see seven half eight, though it'll take a lot of things to get there.

Dan Denning: Can I ask you a question about that because I think it's important for BPR readers. We talk about political risk a lot. India is the largest democracy in the world. It's geographically diverse, it's religiously diverse, it's politically diverse, it's linguistically diverse. It's a real melting pot. In your view, when you guys look at it as an investment question, you may talk about this later, so if I'm preempting you my apologies, but where is the risk in India? Is it political? Because from what you're saying here, divided government's probably better for the market or is it demographic and social?

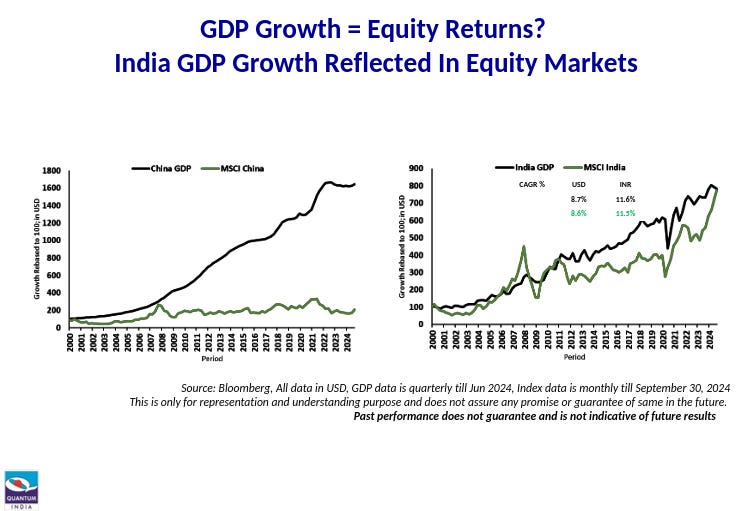

Ajit Dayal: I think there are two risks, and I think you hit the nail on that. I'm going to show it in the next chart, actually. You did hit the right point. This chart on the left side, we have China's GDP growth plotted in the black line and the green line on the left is MSCI China index in dollar terms. On the right side you have India, the black line again plots GDP growth, and the green line is MSCI India index returns in dollar terms.

Now, if you look at this, a few things hit you straight. GDP growth rate in China has been phenomenal. Look at the scale from a hundred, you've got to 1600. On the right side, India's hundred is 800 same time, right? China's grown in that sense twice in terms of end result compared to India.

But look at the share price returns in China as measured by the MSCI China index. There's no correlation between GDP growth and stock market returns, which is the reason why we invest in any economy generally speaking, is when there is GDP growth rate growth, you expect that there will be growth in company revenues when there's growth in company revenues, all else being equal, you'll have growth in operating profits of companies. When you have growth in operating profits, you have growth in earnings per share, you have growth in earnings per share, you have a growth in share prices. That's the common logic as to why we look to invest in areas of the world that are rapidly growing because you want to benefit from that rapid growth.

Well, you know what? In China, you don't seem to get that benefit in the public markets. You may have done it in private deals and venture capital, but certainly not the public space. The public markets are the ones that are the most accessible and the most liquid for any investor to get in, get out. You don't need connectivity to be invited to be in the best venture capital fund or the best fund or have a $10, $20 million slug of capital to invest in those funds.

But when you go to public markets, you can buy a fund on the New York Stock Exchange or any fund approved by the SEC, a thousand dollars, $2,000, $10,000, 50,000, whatever number you want. It's not a high cap. But look at the India correlation, very strong compared to the China correlation. This is what we spoke when you asked about the risk in India. We prepared these charts prior to the May 2024 elections six, eight months ago. We prepared these charts to indicate that everyone wanted strong man Modi to win again.

We said, "No. The reason why you have this disconnect in China is assume you're Jack Ma and you said something bad about the government, you get a tap on your shoulder, you're taken away for a few months, your brains are rewired, your company's shareholding is rewired, your company's revenue streams and business contacts are rewired and it's taken away by the Chinese state or some of the friends and families of the Chinese state."

Therefore, the public market just lost a rate of return that Jack Ma would've in a free world been able to capture in Alibaba, Alipay as an example. In the case of India, we don't yet have that. We have enough cronies and that's why the integrity screen that I refer to is important to make sure you leave the home country of the US and you invest in a distant land and then you end up investing in cronies. That doesn't make sense.

Cronies can come and go and governments can change, but our fear factor was that if Prime Minister Modi came back to power on his own, as I showed you that black line graph and the black lettering, then he would be a strong man. In this chart we've taken Brazil on the top left, he spoke about the BRICS, Brazil on the top left. We've taken Russia on the top right, we added Turkey because we have China on the previous slide on the bottom left. India again for good measure and a reminder on the bottom right.

The reason we chose Brazil, Russia, Turkey, China was because of commonalities. They had strong men, strong leaders in power. Everywhere we have a strong person, a strong leader, there's a disconnect because in Russia, if you say something bad about Putin, you are shipped off to Siberia. Your assets of aluminum or oil or gas are taken away from you and given to the state of friends and family or Putin.

Same thing in Turkey, you say something bad against Erdogan, he doesn't like what you said he owns 99.5% of the media is owned by his friends and family. Our fear was that if Prime Minister Modi won the third election on his own as the BJP, as a sole party, you would end up in that direction because you've already seen a drift of crony capitalism. Crony capitalism is everywhere in the world including the US, but we were seeing a sort of increase in market share, if you will, of regulatory capture of a few of the crony groups that exist in India. That's what our integrity screen tries to sift out. I hope I gave you the answer. One risk, which seems to have faded the political risk of having a strong man that's gone away for now.

But the other risk that you spoke about about the demographics and social, that's very, very real and it's there. When Goldman Sachs came up with this BRIC report in 2000 5, 6, 7 and glamorized the fact that India had a lot of people, and there are still a lot of articles on that about the demographic dividend, we looked hard at the data and said, "Well, you know what, there are 10 million people looking for a job every year."

That's roughly 27,700 people looking for a job every day coming into the workforce. If you do not find them jobs and they're 24 years old and 23 years old and 25 years old, there'll be chaos. The Arab Spring will look like a Sunday picnic. The Arab Spring was the uprising in 2002 three, which led to changes in certain parts of the Middle East and North Africa in terms of political regimes.

But that, to us, are the big issue, that since 2004 five when the demographic dividend was discussed. Who's talking about avoiding a demographic disaster? I'll take the US as an example, and the OECD broadly speaking, in the United States that are 10,000 people retiring every day in the western world, Canada less so, but more Europe and Japan. You've got a pension problem. The pensions are underfunded and the obligations are more because people are living longer and the healthcare costs are increasing. The pensions have a problem of paying you enough money to live a certain lifestyle. But if 10,000 people retire every day, and let's take a population that's 85 years old and 90 years old and is getting a pension check of a hundred dollars a week, for example. If the pensions are underfunded and instead of sending a hundred dollars a week by obligation, they send you a check of $70 a week, what exactly will you do as a ninety-year-old individual in America?

Not much. You're not going to go and fight on the streets. You're basically going to fade away. You'll have to figure out what to do, but there's nothing much you can do. But in the Indian context of young people, you are energetic, you want that job, you are eager, you are upset. There'll be riots on the street.

We just had our budget in India or last Saturday, February 1st, and we look at one indicator. That one indicator we look at is how much is the government spending on hundreds of millions of poor people? This time the answer is 1.3% of GDP and it tends to be between 1.2 and 1.3% of GDP. We keep on looking at that. If the government spends that 1.2, 1.3, 1.5% of GDP, you are buying time. You're paying these people enough money to live and survive until the government or you the private sector have figured out how to empower them with skills and to get them jobs.

That is India's only risk today. I spoke about the political risk, of course, which comes every five years and comes in every economy during election time. But this is a fundamental risk. There's a people in the CFA world and the MBA world that I come from, people assume that volatility, the up and down movement of share price or a market is risk. That's not risk, just standard deviation volatility, something going up and down.

Risk is an economy that implodes because of social unrest. Risk is investing in cronies, in crony capitalists who steal from minority shareholders. Those are the risks that we try to sift out and look at and worry about when we invest in India. I'll just flashback in history a bit. In 1990, I was all of 30 years old then I just started Quantum in the month of February.

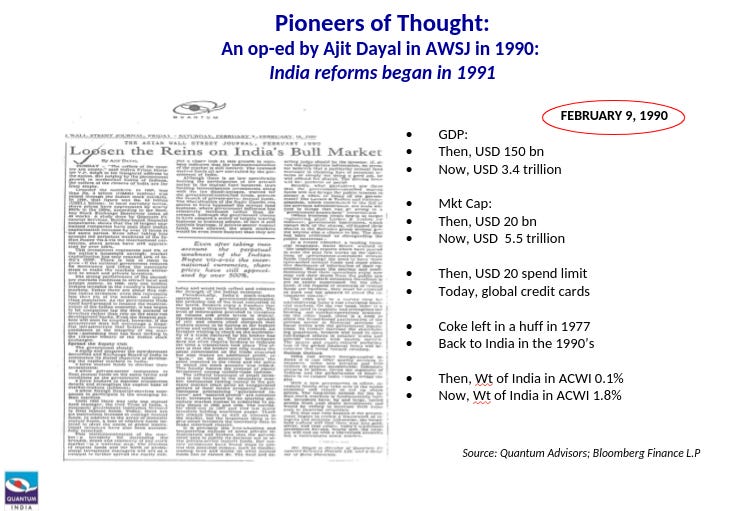

I wrote an article for what was then called the Asian Wall Street Journal. Now of course it's just the Wall Street Journal. I wrote, as you can see from the title, Loosen the Reins on India's Bull Market. It was a plea to the government that, listen, India's ready to thrive, just reform, give us reforms. In 1991, July 18 months roughly after I wrote the article, we had the best reforms. India had seen the big bang of India's reforms. That's what's led to this massive run up in India's presence. Still, as I indicated, very small compared to China, but compared to where we were, we were inconsequential a one $50 billion economy today, 3.4 trillion at that time we were in stock market terms, we had a 0.1% weight in the all country world index Indian stock markets represented 0.1% of total market cap in the world.

Today, we're nearing 2% and probably going to rise as GDP increases. India's on its way to exercising its space in the global stage. I'll jump a bit if I can to my years when I was living in working in Florida with Tom Hansberger in Fort Lauderdale, in Florida, where Tom Hansberger, who was a co-founder of Templeton, Galbraith, Hansberger, and then when they sold to Franklin, the firm changed and Tom set up his own shop called Hansberger Global Investors in '94. I met him in '97 and he invited me to come and learn value investing from him.

I got to live on a beach, which is a great deal, a fantastic time in Fort Lauderdale. I got to drive three miles to the office every day and learn from Tom value investing. While I was with Tom, Vanguard hired Hansberger as the outsourced manager for their international value fund in July 1999. I'd gone there for the final pitch to the Vanguard headquarters. People don't know, but about a third of Vanguard assets, quarter assets are actively managed. They don't only have ETFs, they don't only have index funds.

Dan Denning: That's surprising to me. I didn't know that. I just thought it was a passive indexing strategy.

Ajit Dayal: It is, but they always try to find something cute and something nice, which they can't replicate on an index. They found us as a value manager for that. They hired Hansberger and they said that I should be the lead manager on the account. I learned from them what is the most important thing for an investor to figure out about an investment firm?

These were the four P's because I asked them, "Why did you choose Tom? You have hundreds of managers to choose from. Why did you choose Hansberger Global Investors as your outsourced manager?"

They said, "Well, we know Tom's history, we know the people, his history of what he did with Sir John Templeton creating this phenomenal firm which is sold to Franklin. We know the philosophy, long term value investing. We know the research and portfolio construction processes to convert that philosophy, whether rubber hits the road, to ensure that you indeed are picking value stocks."

Show me your research process. Show me your portfolio construction process. Most importantly, once I see that you are a value manager, I have a certain expectation from you. I know when the Magnificent Seven are doing very well. In those days it was Nasdaq, it was 1999. When Nasdaq was doing phenomenally well, we expect you as a value manager to underperform. If you outperform Nasdaq in its .com bubble days of 1999, then you are not a value manager. You're doing something strange and I'm going to fire you. I'm going to retain you because you're doing what you're supposed to do, because I also have a growth fund. I have a Vanguard National Growth Fund, and the growth manager better do better than Nasdaq, not you. You have basically you have the building blocks of asset allocation as I spoke about India. What is India's weight and the global global GDP going to be?

What is China's weight? Should your portfolio reflect that? What should an asset allocation be? In a very similar way when you allocate capital to a manager, the manager better behave in a particular way. It's that predictability, not the number, but the predictor pattern. If you read in the headlines, "India is doing very well and markets are at an all time high," you should expect the value manager to be selling trimming and underperforming because cash doesn't increase in value like a rising stock market week after week. You should expect that.

When you read that India's in a bit of a crisis and the markets are coming down, you should expect the value manager rubbing his hands or her hands with glee and saying, "You know what? I'm going to invest more capital because I see more opportunities." Also, because he built a value portfolio, the decline should be less than the market, broadly speaking. That's what they taught us in terms of the print.

Dan Denning: I just wanted to add a quick point on that, that when I started working for Bill in 1997, tech started out performing everything else including value. They were different tech stocks, technology, media, telecom. There was a famous value fund manager whose best performing position was America Online for two or three years in a row. I always thought it was a bit of a misnomer that he was calling his fund a value fund when his largest position and his best performing position was a media stock. It's an important thing to look for.

Ajit Dayal: Absolutely. Since you mentioned that, I'm going to just talk about and relate to this, the integrity screen. A year before I was starting Quantum 1989, I was 29 years old, I met a gentleman from South Africa who worked for Credit Suisse. I wish I remembered his name so I could quote his name out here.

He asked me, he said, "Young man, what do you wish to do?" I said, "Set up my own investment firm," which I did in 1990. He said, "I have one piece of advice for you when you shake someone's hand and you get your hand back, count your fingers. If you don't have five fingers, don't shake their hands again."

I didn't quite understand what that meant. I set up my firm in 1990, I did a joint venture with Jardine Fleming, and we actually launched a New York Stock Exchange listed fund, a Jardine Fleming India Fund way back when in 1994.

There were things going wrong with crony capital and some of our investments. I didn't like the way founders were behaving and I wanted to sell the stocks and my partners did not want to. I just left the joint venture. I couldn't handle that integrity screen violation, if you will.

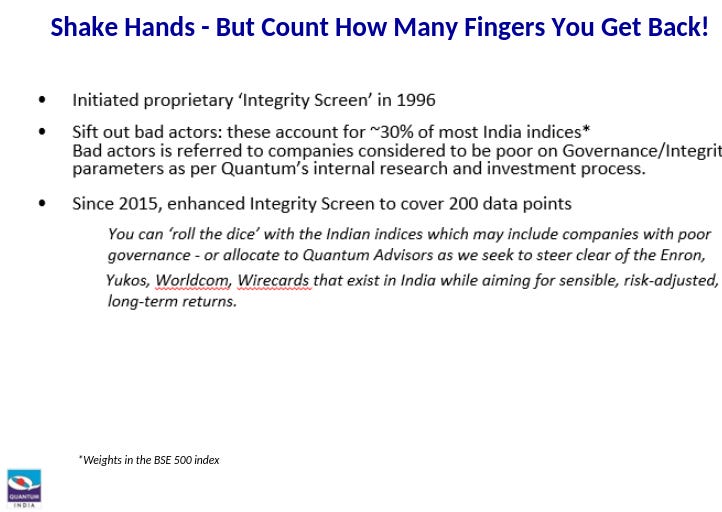

But when I left the Jardine Fleming joint venture at the end of '95 and came back, Quantum 2.0 version in 1996, and Subbu, my existing partner and work partner since now 29 years, joined in 96, we put up the integrity screen. This was a way for us to not only understand valuations of a portfolio, we hadn't met Tom Hansberger yet, but we understood valuations. We were not value investors per se, but we also recognize there's certain protection of minority investors or certain behavioral patterns of companies that could harm us as investors and companies.

The integrity screen was started in 1996, and if you look at the indices today, whether it's, I don't want to give names, but the indices that are popular which track India, 25 to 30% of those indices have companies in them that fail our integrity screen. Their integrity score is low, and we will not be buying their stocks because we don't think they protect the rights of minorities. Index investing is a strange thing because I don't think it works in a market where governance is an issue and protection of minorities is an issue. You spoke about that one value manager who held AOL, okay, that was a style drift.

Let's talk about another manager who had Enron. He had Enron as a big position in '99, 2000, and he kept on buying at every decline of Enron all the way down to cents on the dollar and lost much of his reputation because of that one bet. Because Enron would've failed the integrity screen and integrity score if you had really studied Enron and tried to figure, of course, very, very few people knew what was happening.

But if you had managed to figure out Worldcom, Enron, as I mentioned here, Yukos and those equivalents exist in India very much today. They're thriving and they're flourishing in India today, but we stay away from them. That's why this integrity is important.

Then the valuation metrics that Tom Hansberger taught us, which we exhibited when doing the Vanguard International Value Fund and Tom's other global emerging market portfolios when I was Tom's partner. Then we broke out a 2004 to Quantum version 3.0 and raised capital under our own brand name for the first time since our birth in 1990. Literally, 14 years later is the first time that we raised capital in our own name. We've integrated that valuation with the values of an integrity screen, if you will. That's something that's, I think, quite different about us from many other managers, not only in India, but I would say in the space that we operate in.

Dan Denning: Is that partly because the equity market in India is suddenly become much more interesting to global investors or purely because of the number of businesses that are listed companies, just to keep up with them would be difficult, but you have to add this layer to make sure it's a real company with good managers?

Ajit Dayal: No, you asked about risk, and I think risk is, as you mentioned, the political risk of having strong man leader who deviates you to Putin style, Xi style policies and Modi was that risk and is disappeared down. Then the other risk I spoke about was job employment creation and the demographic disaster that could happen. The other risk, of course, is that you, as I said, you leave the laws of the homeland in the US and you invest in India and then you suddenly find that some guy's getting rich, but you're not getting as rich as that person who's a founder of the company. You ask yourselves why?

Well, because they're taking money away from you. They have third party related transactions with private companies where they get supplies or they sell goods at non-market prices and they're stealing from you effectively. I think that's a real risk.

I think for us, when you look at the India opportunity, much as it may look exciting to invest in an airport, for example, or in a port and you say, "Wow, this is going to be fantastic," or a toll road, there's going to be more traffic and more goods and more people, and that's all fantastic, but you have to ask yourselves the question, "How did that person get the license to build that airport? How did the person get the license for the telecom business?"

If you think about in the US you have a lot of cable companies and telecom companies, and it may be more of a freer market, but it's still a regulated market. You can't just come in and do what you wish to do In India also it's more regulated. You can't just do what you wish to do. There's regulatory capture.

The mobile phone market is not a question of who is actually buying the best mobile service. It's a question of who's captured the regulation for the spectrum, for the mobile service. It's not about who's got the best airport, it's about who's captured the license to build an airport in a city and ensure that no one else will come anywhere close to them, giving them a monopoly of all landings in that area.

If you question that, and if you don't find that to be transparent, well, you know what? There are elections every few years in India. It's a democracy as you said, and governments can change, and tomorrow Ajit may be the favorite party of the new government and the license of the old guy can just go away and be given to Ajit.

That's a real fundamental risk. We measure risk very differently, like I said, it's not that... It does hinder our opportunity, of course, because we're not investing anywhere we wish to. We're investing in companies where you can trust the management not only to build a good business, but to actually ensure that you get your fair share as a 0.1% or 1.2% or 10% shareholder in the company. That's important from our perspective.

Dan Denning: That's a great point. I want to ask you about the other, well, maybe the other side of the coin with that, aside from risk and integrity, which are filters that dictate what you're going to invest in and what companies make the grade. The other obviously is valuation.

I wanted to ask this question in the context of what US investors are dealing with here. That as you know, since 2008, really since the US housing market collapsed, and you had this incredible response from the central bank in the form of lower interest rates and quantitative easing…US dollar denominated assets, stocks and bonds, but more recently just stocks have just crushed everything in the world globally.

As a momentum play and as a growth play in the last two years, really the last four but more the last two, it's even more concentrated in large cap US tech, what we know historically, and I'm sure you know this, is that when you've had a decade of extraordinary returns that ends with a peak in valuations, whether it's price to book, price to sales, market cap to GDP, dividend yield, all these traditional measures of whether stocks as an asset class are expensive or cheap, we know they're expensive in the US and that the next 10 years of returns are likely to be below average or below historical average.

Is that the main driver for American investors to look at Indian equities now? Or is it that the valuations in India are much more compelling than they are in the US? Or is it some combination of both?

Ajit Dayal: It's a combination, but I think very broadly speaking is going back to what we spoke about earlier. When GDP is increasing, so you have to look around the world and see where there's growth. Growth is a wonderful tailwind for management of companies to grow businesses and to have better profits and better stock market returns. Of course, to that, you had the integrity screen and you had risk of currency, political stabilization, destabilization, etc, etc. But you're looking for growth pockets. The US is clearly one growth pocket in the world today, and China's a slowing growth as we showed where China was compared to India. It's already had 10, 20 years of advantage of growth compared to India in many fronts. On the other side, if you look at India, it is a growing market. Of course, Africa, parts of Africa are growing.

Japan is not growing, Europe is not growing. Where do you invest? You invest where there's growth and that's that correlation between growth and stock market returns, the charts that we showed earlier. You invest in India also because history suggests that economy that has grown twice that of the global average and probably twice that of the US has.

We've got this chart from January one or December 31st, 1999. From January 1st, 2000, we've shown you the Indian indices. The first three are Indian indices. The first two are local indices of the Bombay Stock Exchange. Then you have the MSCI India in the green. Look at the MSCI India in the green and look at NASDAQ below that and S&P close and emerging markets in the red and China depicted to the Shanghai Stock Exchange composite, all in dollars. After currency lost and Indian rupees lost roughly three, three point half percent against the US dollar in this 24 year time period.

But look at the end point, the end point of the MSCI India index and the end point of the S&P and the NASDAQ, we've done better in dollar terms and that's because Indian GDP has done better. Of course, there are moments in time, you mentioned the Magnificent Seven where NASDAQ or parts of the US market will do far better than India, but over decades see the compounding factor of just being invested a market more.

You could see India, if you look at the volatility, the jump of the green in 2008 after Lehman, the fall in the green was also significant percentage terms as it was in the US. It's a lumpy chart, but you have to be very patient and you have to understand initially why you invested. It's the thesis of investing and selecting the manager and the fund, still the same.

If it is, then just stay committed because the underlying story hasn't changed. It's a combination of GDP growth rate and opportunities that come along with it. I think governance matters. I'm not able to show our track. We've got a long track record of 24 years, [inaudible 00:45:26] are coming up. In fact, we are not supposed to show our track record here, so it won't be there. But it's an interesting market to look at.

Just look at the indices, right? The indices and I mentioned the indices have cronies in them. Despite that, or maybe because of that, whatever they've done pretty well, but it's a compelling place to be. I think if you try to figure out what's happened in the Indian space, what are Indian mutual funds? The mutual funds are a relatively new idea in India, only started in 1993. We had a government of India Monopoly, not even a mutual fund, a fixed rate of return kind of product for decades from 1964 until 1993.

Then we opened up the mutual fund industry in India, 1993. If you look at the flows, the blues are positive inflows from domestic retail investors into mutual funds, and the reds are redemptions. On the left side you can see it begins very slowly in 2003, that's like 10 years after it first started. Then you had the BRIC meeting in 2006, 7, 8, and you can see the surge in blue. Then you had the collapse of Lehman in the red, we circled a ten-year blank. It's a seven, eight year blank where people were redeeming from Indians had lost faith in their own market, if you will, at their own economy. Modi wins. He inspires a whole bunch of Indians to think of India as a superpower and brings a lot of know gumption, if you will, to the Indian speech and Indian volume. You have that flows that are turning very positive, and of course Covid everywhere in the world, you had redemptions for a while, but look at the peak flows that are going on.

When you juxtapose this with what the foreigners have been doing in that same time period, the blue line shows the foreign portfolio investors, called FPI's in India. You can see their line was going pretty upwards. The Indian line, the domestic funds were flattish and then that surge, and you can see that money. Money flows with GDP growth rate with company earnings has led to PE ratios being relatively expensive compared to their long-term average of 20 that started in 2001 as per this chart.

That had been periods during SARS in March 2003, which was the first pandemic in global modern history and global capital market, his modern capital market history, Lehman, of course the GFC, and then Modi gets elected at the trough, if you will, of the Indian market and the domestic reasons.

Then Covid and other pandemic that hit us badly. You can see how certain points in time the markets look really attractive. As a value manager, one would expect to find better opportunities when markets are less fancy, and have fewer opportunities if you're disciplined. The disciplined research investment process, I spoke about the Vanguard four P's, you would have less opportunities when markets are too excited.

Dan Denning: Can I ask you a question about this chart really quick?

Ajit Dayal: Yeah, absolutely.

Dan Denning: Do you expect the E part to get better in the next 10 years? The earnings on the multiple will come down because the earnings are going to go up less than-

Ajit Dayal: We had seen a decade of not much good earnings growth. Funnily enough, from the time Prime Minister Modi became prime minister 2014 until about 2000... Well, let's keep Covid out of it. 2019 and March 2020. For those six, seven years, India's EPS did not grow much at all.

Then of course there was a big Covid rebound of EPS, but it's only now that you can start seeing EPS growth being better like it was in the previous decades. We had subpar EPS growth and a lot of flows coming in, which is why you've had this expansion in price to earnings ratio because the EP has not kept pace with the flows of money related to the expansion of PE. But again, if you go back a longer time in history, 30 years in history, 35 years in India's history, there's a very remarkable correlation between earnings per share, the earnings per share growth number of the index, and the level of the index, just how we saw the GDP chart of India with the MSCI India index returns in India.

We had the very similar chart of earnings, so there can be dislocations. Those dislocations are where, as a disciplined investor, as a disciplined manager, you take advantage on behalf of your investors and your clients to file in or jump in or step out as the case may be if things look a bit awkward in terms of valuation.

Also, just to close that topic on valuation. Within the market, there are certain sub-sects, small cap, mid-cap where P/E ratios are significantly higher. There's been a correction the last couple of weeks and months, but there's still a gap between what the small cap and mid-cap people are dreaming. There's a new company born or new company doing an IPO, and oh, they're going to take over the world, they're going to take over the optimism and the flows from that optimism.

A lot of it is unwarranted. What we've seen since the last few months, we've seen the MSCI India index correct by about 17% in dollar terms, but after having a exceedingly phenomenal ride in a post-Covid recovery. Yes, the US market has the Magnificent Seven, and we did a chart of the MSCI US index. You can see there's a complete surge in the index. Why?

Because US companies don't only rely on US GDP for earnings. The Magnificent Seven are relying upon a global audience for their growth. You have that surge in the index of the MSCI US, and if I had that chart to show you, it would be a dramatically upward sloping chart breaking away from GDP completely opposite of China, where you saw GDP high and market cap market index low. The American one is opposite because of the fact that Facebook, Meta, Alphabet, Google everyone the global, they got a global audience unless there are rules and that is put in as in the case of China, etc.

Dan Denning: That's a great point. It makes it hard for when you're using different factors to determine your style or to conform to the style where you say, "Well, it's a US company, but it derives a bunch of its earnings from foreign sales."

I want to shift a little bit to the fund itself that you have and the construction of the portfolio that when you're talking about this difference in valuations between the small caps and mid-caps. When I started out working for Bill in the late nineties, the growth stocks were all the rage because that's where the money was to be made.

Everybody wanted to make as much money as quickly as possible. They were willing to pay a large premium for companies who were capable of growing earnings and profits at a double-digit rate. I'm sure that's not the case with your fund based on what you've said, but can you tell our readers a little bit more about the number of positions that are in the fund?

Are they large caps? Are they mid-caps? Are these companies that you can buy through an ADR or some other US vehicle? Or are there things that they can get through the fund that they're unable to get in the US? If so, what makes it more attractive for US investors?

Ajit Dayal: From our strategy and our approach perspective, when are often asked the question, "What's a guy like you doing in a place like this sort of thing, what's a value manager doing in a growth market?" A value manager doesn't mean that I'm buying distress. A value manager means I'm buying the growth. I believe strongly in the India story.

I left the US in 1984 after my MBA to go back to India to a dead economy. I began working and preparing Quantum's birth effectively and then fighting for the reforms in India. Then after being trained by Tom again going back to India, I could have been living on a beach in Florida having a great life as Tom's CEO and heir apparent of his company and growing the business on a global basis. But India is my heart and soul.

India is where the growth is, and I see it and we all see it, actually now the world knows about it, but we are very careful about the valuations. I indicated about the governance levels and protection on minority rights. You can fight for protection of minority rights in the US in a faster way and a quicker way. In India, you go to court, it'll take decades, right?

You have to be careful on the way in, do your due diligence before you jump in very carefully. Luckily, if you're on a liquid market and public markets are liquid in India, you can exit the stock if you make a mistake, unlike venture capital, private equity if you make a mistake or stock.

But to go back to the thing, so as a value manager, we also worry about liquidity. That is the underlying stock that we're about to put client capital in, is it liquid? The reason why liquidity is very important, and you can go back and look at what happened in the BRIC period and after Lehman, is that many small cap funds that were launched for India invested in small caps. Their NAVs were decimated because it shares were so illiquid when the fund manager began to exit the stock, the act and fear of the exit or volume brought the price down of the small cap stock by 80 to 90% with a very fractional volume of transactions because the fear was the person going to offload.

There are some small cap funds in India, and we've done a study on this. There are some small cap funds in India, which a few months ago had in their top 10 positions, stocks, which would take anywhere from a hundred trading days, which is nice. That's our rule is 90 trading days.

But there are some stocks that would take 3000 trading days to exit in a market which trades 220 days in a year. 3000 days is like 14 and a half years to exit that position. You can imagine when they go to sell that stock because there's a redemption and they have to meet the redemption, they're killing the NAV.

You read, you go to the website and you see the NAV of the fund and you say, "I want to exit. It's a good NAV." But then you go to place a redemption order and many people do the same thing and the fund manager goes to sell. By the time he sold the stock, the NAV that you saw and the NAV at which you actually redeemed, there'll be a gap. You could see that in the Lima tab. We have a rule of liquidity.

We have valuation integrity score, integrity screen and score and liquidity. Then if we end up in small caps, that's fine. We have no problem buying small caps as long as we meet the liquidity criteria and valuation integrity screen. We don't have a focus on market cap. Our ideas, how do you find great value of good businesses which are going to make money in a sensible way and share with investors, with minority investors without stealing from them and give me the option to exit that stock, deploy capital or exit that stock without moving the price.

When you look at the universe of available India managers and you begin to evaluate them on different criteria, those are the ones that we apply to ourselves. Of course, people have different methods of selecting a manager. I spoke to you about how we have built Quantum based on the four P's of Vanguard and making sure that we really have that fifth P, which is patient long-term capital that doesn't get scared of market movements if the underlying philosophy and the underlying thesis, and the underlying care taking of the portfolio hasn't changed.

Dan Denning: That's a fantastic point. Those are fantastic pillars for an investment philosophy. I know that Tom Dyson, our Investment Director, has tried to adopt some of that with our risk rating, which we assign to positions that we follow. Liquidity is a huge part of that. The last thing you want to do is either move the market or not be able to sell when you're ready to sell or to get a different price than what you think you ought to get. I'm glad to see that that's an issue that you guys have addressed from the bottom up. By the way, I have let Tom know to get in touch with you and your team.

Ajit Dayal: Fantastic.

Dan Denning: Another point that I think our readers will appreciate that we have what we call a Trade of the Decade, which is a ten-year perspective on something that we thought was very cheap, which will be much more expensive or fully valued over a period of time. The chart you showed going back to 1500 tells me that maybe we should add a trade of this century to see India and China are gradually and then suddenly reemerging as global economic powers. That that might not be fully reflected in the valuations of the companies.

To find those companies, you've got to do the work that you're doing. I wanted to remind readers in case they forgot from when we started, if you want to find out more about what Ajit and his Quantum friends are doing, go to Qasl.com and then click on the India fund and you can read more about both the construction of the portfolio, the minimums that investors can put into the fund and find out more information about how to participate in this story.

Every country has a home country bias and for whatever reason, investors don't want to hear about stocks in other countries. They get confused about the risk, whether it's political risk, or currency risk, or regulatory risk, or just how to easily invest money in another country that shouldn't get in the way of a compelling opportunity when you see it. I thought this was a great time for you to talk to our readers about what you're seeing in India. Is there anything else you want to add before we wrap up? We're near our one-hour hard stop.

Ajit Dayal: I remember in 2006, Agora bought a busload of people to India on a discover India tour holiday and come and meet company's holiday. Come over and see what's happening in India. Plan a trip again. It'll be fantastic to host you there.

Dan Denning: All right, well, we'll get on that. I'm going to go see Bill right now and don't be surprised if you see us. But in the meantime, thanks very much Ajit. We'll be in touch soon. Thank you.

Ajit Dayal: Thank you very much for having me. Thank you everyone for listening. Thank you so much.

Great interview. All of what he said is so true. Crony capitalism, which every country has. Liquidity issues. Great stories but small purchases/sales drive price volatility. I have bought companies on reports and recommendations from advisors (Agora) or other sources. All looked good until I received the quarterly report and looked at the management team. Rolling stock options usually 10% of outstanding shares. Now RSUs & PSUs. Signing bonuses. All of this creates dilution to the ordinary share holders. Change of control rights for company executives to stop these grifters from being evicted or raising their bonus payouts for agreeing. Directors earning exorbitant fees when the company isn’t profitable. Last but not least an executive being paid as a consultant. When I discover these things I exit. Activist investors should go after the boards who are supposed to be looking after minority investors by ensuring that the executive & board aren’t in collusion for their own enrichment.

Great interview. One of the biggest economies and part of the BRICS.

Foreigners are limited to ETFs or ADRs - no direct access to Indian stock market, banks, or even hold rupees. (except in Wise Payments or Everbank CD)

Difficult for Brazil and South Africa too. Russia is blocked. still have delisted Gazprom shares.

Tom is there now, perhaps he could do boots on the ground reporting and investment opportunities.