Inflare aut mori

No government has ever succeeded in improving an economy…other than by avoiding war, providing some rudimentary justice, and removing the impediments set in place by government itself.

Friday, November 14th, 2025

Bill Bonner, from Baltimore, Maryland

The problem with the busy-bodies is that they are too busy. TV…tablets…TikTok — who has time read the classics, or to think at all?

An example: the destruction of the twin towers on 9/11 will bring some “economic good,” said celebrity economist Paul Krugman. “Now, all of a sudden we need some new buildings…rebuilding will generate at least some increase in business spending.”

Holy schmoley…hasn’t this man ever heard of the ‘broken window fallacy,’ the classic economic text by Frederic Bastiat? Digging a ditch, filling it up…and then digging it out again…does not make you better off. It is a loss…a waste of precious time and energy.

Every economic problem we face today has been faced before. Overspending, corruption, debt, panics and crashes. Every obvious ‘solution,’ dodge and fix has been tried, too. Some within the living memory…and some two millennia ago.

But no government has ever succeeded in improving an economy…other than by avoiding war, providing some rudimentary justice, and removing the impediments set in place by government itself.

It’s all there…the whole story, a tale of sweat, sin, mistake, genius, and luck…in more than 2,000 years of recorded history.

Why not learn from it?

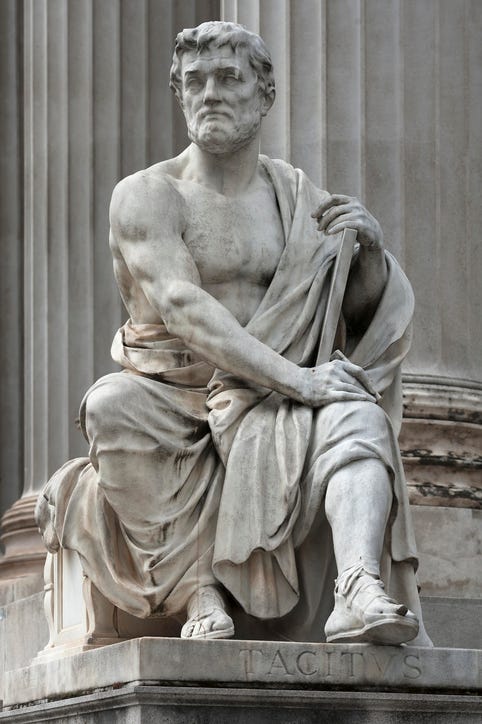

A love of learning from the past took root early in the American colonies. George Sandys, in the 1620s, completed his translation of Ovid’s ‘etamorphoses on the banks of the James River. Robert E. Lee’s great grandfather, Richard Lee, was a man of great energy and practical achievements, but he kept his notes in Greek, Latin and even Hebrew…and was said to spend his free time in his library, reading Plutarch, Tacitus, Virgil and Homer.

The aristocratic planters of Virginia kept libraries both as status symbols and as places to learn. William Byrd had the best library in the New World at his place, Westover. Like Lee, Byrd read Latin, Greek and Hebrew.

Thomas Jefferson began studying Latin, Greek and French at nine years old, under the direction of a learned Scot, William Douglass.

“I thank on my knees,” Jefferson wrote in later life, “him who directed my early education for having put in my possession this rich source of delight, and I would not exchange it for anything… that I have acquired since.”

John Adams read the classics too. “When I read them,” wrote Adams to Jefferson in 1812, “I seem to be only reading the History of my own time and my own life.”

Of course, neither Adams nor Jefferson stopped with Plutarch. What they got from them was a curiosity and intellectual confidence that allowed them to move on…to Milton, Shakespeare and Johnson. And being able to read French, to the early economists — Colbert, Say, and Turgot.

Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, the Baron de l’Aulne, read the classics too. He translated the Aeneid into rhyming hexameter! He read French, Italian, Latin, German, Hebrew, Greek and English. As a 22-year-old, wrote Andrew Dickson White in 1915, his letter explaining inflation, “remains one of the best presentations of this subject ever made…it was reserved for this young student to lay down for the first time the great law in which the modern world, after all its puzzling and costly experiences, has found safety.”

The general principle with which Turgot is credited is the ‘law of diminishing returns.’ As it applies to inflation, the more money you print, the less each additional unit is worth.

But the modern world found little safety; the TV watchers of the 20th century have largely forgotten the classics…and even in his own life, Turgot’s insights were rejected.

As Comptroller General of France he was a Javier Milei without a chainsaw. He advised the young Louis XVI to reduce taxes, cut spending, avoid debt, eliminate trade barriers of all sorts, and balance the budget.

Had his recommendations been followed, France might have avoided the Revolution and Louis might have kept his head. But then, as now, the insiders were in control. Turgot was fired in 1776. Jim Powell describes what happened next:

Having rejected Turgot’s peaceful reforms, the French government stumbled from one crisis to another. Hatred bred of oppression boiled over, as Turgot had anticipated. On January 21, 1793, Louis XVI was led to a Paris guillotine and beheaded. Marie Antoinette—ridiculed as Madam Deficit—followed him to the guillotine on October 16, 1793. The French people suffered through runaway inflation, the Reign of Terror, and the military takeover by Napoleon Bonaparte who plunged the country into more than a decade of war.

As for Turgot, so great was his insight…and so deep was his learning…that Pierre-Samuel du Pont de Nemours (father of E.I. Dupont who started the chemical firm headquartered in Delaware) said of Jefferson that he was the “Turgot of America.”

But all of them — the great thinkers of the 18th century — found what they needed to know in the observations of other thinkers hundreds of years earlier.

How about stimulating the economy…by ‘printing’ more money? Suetonius (69AD – 122AD):

‘Byy bringing the royal treasures from his Alexandrian triumph [the loot from his victory over Mark Antony at Actium], Augustus made ready money so abundant the rate of interest fell, and the value of real estate rose greatly.’

And how about Trump’s proposal to hand out $2,000 — supposedly the bounty from his tariff wars — to every citizen? Been there, done that, says Suetonius:

‘[Augustus] often gave largess to the people, but usually of different sums: now four hundred, now three hundred, now two hundred and fifty sesterces a man.’

The ancient Bernankes and Greenspans were no strangers to panics and bailouts either. In the Panic of 33AD “creditors demanded payment in full,” Tacitus tells us. And “the more heavily burdened any one was with debt, the harder he found it to dispose of his property…many were ruined.”

But in came the feds. Tacitus:

‘[Tiberius] Caesar came to the rescue and deposited 100,000,000 sesterces in banks, the debtors having the privilege of borrowing for three years, without interest on giving landed security to the state for twice the amount of the loan. Thus, credit was restored, and gradually it was found possible to borrow from private persons also.’

At the time of Tiberius, the Roman currency still had value. It wasn’t until about 100 years later that the end began. The silver was gradually (so it wouldn’t be noticeable) removed from the denarius. By the second half of the 3rd century, Rome’s money was worthless.

Emperor Diocletian was stuck, you might say, between the Scylla of excess spending (especially on war)…and the Charybdis of inflation. Rocks on one side. A hard place on the other.

It was the familiar trap: ‘Inflate or Die.’ Lactantius reports:

‘The number of those who received his pay, growing greater than those who paid him taxes, there was such an increase of new impositions, that those who labored the ground being exhausted by them, they deserted the Empire, and by this means the best cultivated soils were turned to deserts and woods.’

Diocletian wisely retired in 308…and the empire rumbled along…with war, inflation, poverty and crises of all sorts…for the next 168 years.

Today, a cartoon video shows a group of men watching the Super Bowl. As soon as the women leave, the men switch to the History Channel to learn about Caesar crossing the Rubicon.

And a recent TikTok survey revealed that American men “think about the Roman Empire a lot more often than you might realize.”

Probably not enough.

Regards,

Bill Bonner

All those Bookworms of Old... And then there was Benjamin Franklin, Father of Founding Fathers. Indentured servant in his youth, printer by trade, reader by avocation. Indeed... In that era books were valuable items; hand-made in the sense that every page was hand-laid on a press and all the type was hand-set. Even the bindings were hand-sewn. And in a logical flow of proceedings, thus thus did Old Ben "invent" the idea of a lending library by which he and his Philadelphia pals combined their collections, the better to share ideas in those pre-Amazon days.

On the down-side -- but don't hold it against him; it was a necessity of the times -- Ben Franklin the Printer was a promoter of paper scrip to use as currency. In fact, many of the Revolutionary War "Continentals" were his personal handiwork, if not the work of his print-shop while the Man was overseas in Paris, begging funds from Rex Louis and others. But consider that America of that time lacked almost any semblance of hard money. British coins, yes but not many and the Brits were the oppressors. And so Colonials used a smattering of Spanish silver "Ochos" (aka "pieces of eight"), or various other copper and silver coins of French, Dutch and Germanic province... esp silver "Thalers" of Mitteleuropa, products of the mines of Joachimsthal, now part of Czechia. And this is where we get the word "dollar," meaning a round coin that contains just shy an ounce of silver.

And while we're on these points of history... It's fair to say that the founding ethic of the United States of America was penury. The country was abject-broke during the Revolution. Broke during Articles of Confederation. Broke under the Constitution of 1788. And recall that among the first acts of the new Govt of 1789 was tariffs on imports, and then (per Alexander Hamilton) a tax on whiskey stills... this latter led to the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791-94... And along the way the Currency Act of 1792 that established a Mint (in Philadelphia, BTW), and the first US coinage that came out in 1794... The "Flowing Hair" silver dollar, and an assortment of others such as copper pennies... Phased out finally, just this week at the Mint because the cheap zinc items cost all of 4-cents to manufacture.

When it comes to hard money, it's nice to read ancient Greek and Roman writers. But it also helps to read a few books on geology, mining engineering, and metallurgy.

I don't think you are going to force those who voted for Mamdani, the majority, to read Roman classics. There are some people who will read the classics but these are the same people who understand how the government is progressing anyway. Those searching for sensibility. I've come to the conclusion there is only one lesson that will influence society, collapse.