“Try to resist labeling yourself, resist taking on any label because that hems you in. Suddenly, you think yourself as an X. And there's some internal pressure to believe everything that an X believes. And it makes you take sides just based on a label rather than reasoning your way through the issues.”

~ Chris Mayer, manager and co-founder, Woodlock House Family Capital

TRANSCRIPT

Joel Bowman:

Well, welcome back to the Fatal Conceits podcast, a show about money, markets, mobs, and manias. If you're joining us for the first time or even if you're a regular listener, please do head over to our Substack at bonnerprivateresearch.substack.com. There, you'll be able to check out hundreds of irreverent essays on everything from lowly politics to high finance, and beyond. Plus, a bunch of research reports and, of course, many more episodes of the Fatal Conceits podcast just like this one. Not a few of which feature my guest today, a popular guest on the show, and a good friend of mine.

Christopher Mayer is the portfolio manager and co-founder of the Woodlock House Family Capital fund. And he joins me today. Chris, good to see you, mate. How are you doing?

Chris Mayer:

Yo, good to be on with you, buddy. How you doing?

Joel Bowman:

Good, mate. Always good to have a brighten up my day with a chat with you, mate.

Chris Mayer:

There you go. Yeah. Same. Looking forward to it.

Joel Bowman:

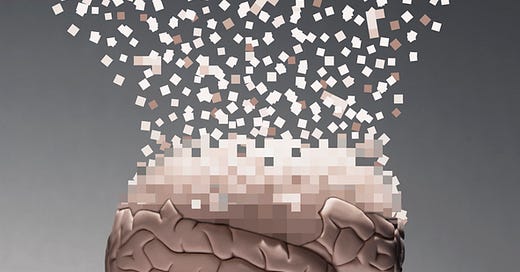

Now, readers and, I guess, listeners now who have heard a few of our previous discussions know that one of the themes that we touch on with Chris as an increasingly rare omnivorous reader is we like to thumb through some of the spines on his bookshelf, see what's got his gray matter, taking and inspired. We've had, I think, maybe three or four of these discussions now. And we've set them up with a few different categories of book, whether it be philosophy, or travel, or fictional, or what have you.

But you had a bit of a different idea today, Chris, and thanks to your recommendation. I've done a little bit of a two-day crash course on your selected author and has turned up some very, very interesting points. So maybe we can get right into Neil Postman and his seminal 1985 work. It's quite amazing to think that this was that long ago, titled Amusing Ourselves to Death with the very appropriate subtitle of Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. (Here’s a link to the book.)

Chris, you want to set the stage for us?

Chris Mayer:

Yeah. So I put this under the category of understanding media or understanding media culture. So if you want to have some framework to make sense of social media and TV news and all the stuff that goes on, this book will really make you think. Yeah. What I think about is this eerily prescient. So, yeah, you said it came out in 1985. It's hard to believe that ... Here's the copy. I'm going to read just the beginning because this sets up the whole book. There's a little part in the beginning where he compares the dystopian vision, Orwell, 1984, and Aldous Huxley, Brave New World.

So it's just one little paragraph. I'm going to read it because this is when he says to himself what this book is about. So it says, "What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book because there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to pacificity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance.

Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we'd become a trivial culture preoccupied with the equivalent of nonsense." So he goes on to say here that this book is about the possibility that Huxley and not Orwell was right.

I mean, already just in there, there's a lot you could already sense, which is we're bombarded with so much information that it almost makes everything trivial. I mean, you're bombarded with so much news and takes all the time. It's hard to make sense of all. So I would say, if I had to sum up the key thrust of this book and what one of the main things I learned about, and we could talk more about it, is Postman really makes you think more about the medium itself rather than focusing so much on what is being said.

But he would say, for example, instead of the content of a tweet that gets passed around a lot, he would make you think about, "Oh, what does that medium of Twitter bring? What kind of conversations does it force us to have or encourage us to have?" I remember one example in the book he gives is, think about smoke signals. If you're only communicating by smoke signal, it limits the conversations you can have. You can't have a deep philosophical discussion over smoke signals. Yeah.

And so if you think of every medium that way, you think of Twitter as a medium, it constrains you in a certain way. There's the obvious character limitation. But there's the whole thing about it, there's the likes, there's the retweets, there's followers. And what conversations do that force you to have? What messages that it'd force you to have? And so that's the thing about this book that really makes you think about.

Joel Bowman:

That's a really interesting and very germane points as Twitter and, of course, Elon Musk, and that whole potential takeover and the debate on whether or not one man should control this particular medium, and just the power of that medium and the power that it has accrued in just a very, very short amount of time.

One of the points that I saw Postman make in an interview ... And this was in '95. So this was 10 years after the publication of this particular book, Amusing Ourselves to Death. So it was really, as you mentioned, I think the right word is eerily prescient because even the terminology that he's using, it almost looked like he had taken stock of the conversation today, and then transported himself back to '95 just to give us a bit of a warning about what was ahead.

But he gave ... I remember he used this point about this technology, particularly communications technology, being this Faustian bargain, where it wasn't just this one-way cornucopia of benevolent gifting that we were the receivers of but we also had to give something in return for that. And a few of the points that he brought up, for example, was just basic social skills when we've got our head in a personalized computer and we're not building a community. How does the medium change the way that we interact with one another beyond just the way that we interact individually with information?

And I think, to your point about Twitter, I mean, that's just such an obvious thing that we can point to and say, "Well, there's obvious echo chambers here, where people and whole communities are becoming just more and more fragmented and atomized.

Chris Mayer:

That's it, yeah.

Joel Bowman:

Do you think that that is somehow catalyzing the political divide that we see today, or?

Chris Mayer:

Yeah, definitely do. I mean, you think about people who can build their own little echo chambers now. You can tailor all your input so that you're only getting the stories that you want to hear. So it definitely is fragmenting that way. And I think also the point about new technologies and new mediums that he makes is that it's not like people tend to think, let's say, for example, when email came along and people tend to say, "Well, just another way to send a letter." But it wasn't, it's not that at all. It's a completely new thing. And it changes everything that went on before. Nobody writes letters anymore.

When TV came along and people, in the beginning, they would have depreciated or downplay its potential, its influence, because for them, they just saw it as what they were familiar with as an extension to that rather than something that really was brand new and changed the game, even though they didn't fully understand it. They didn't fully understand what television would do to politics.

And one of the interesting things, I don't know, I don't think it's in this book, I think it's in another book, Technopoly. He talks about the Lincoln-Douglas debates.

Joel Bowman:

Okay.

Chris Mayer:

And they would go on for eight hours. They'd go on for hours, right? They didn't have television. They were there. It was like an event, you'd sit and then have intermissions. And the other guy would talk and they have an hour and then you'd have an hour to respond or whatever it was. But we have TV now. What does TV do? Compresses it, makes an entertainment, we have commercials. And now we do these debates and they have two minutes to respond. It's ridiculous.

Joel Bowman:

Yeah, sound bites.

Chris Mayer:

What's your solution to the Middle East? You got two minutes.

Joel Bowman:

Be concise, make it snappy. And also, I think, to your point there about this participating in person in communal activities, Postman refers to it as the co-presence of communications, where you are literally ... I mean, you and I are talking over Skype here for just want of geographical closeness. But there is something radically different from, let's say, attending. We were at the theater down here just last week with my wife's dad who was visiting in town. And we took him along to a show. We saw Giselle.

I mean, it's an incredibly different experience when you go to Teatro Colon down here. It's a packed house. People are there, they're clapping in unison. It's very, very different from we took my seven-year-old daughter along and she'd seen some performances on the television before. But this was just a whole another world. And so it makes me think, given just the past couple of years and how these kinds of rolling lockdowns and interruptions to global travel and just almost the wholesale cancellation of the public space, how that might have affected the way that we digest our information.

Chris Mayer:

And I don't think we really fully understand it yet. That's the other thing is even social media, it's been around a while now. But I don't know yet that we fully appreciate and understand it, what its impacts are and how it's changed things. It took decades before people really figured out TV and how to use it and what its effects were and, yeah, it may take some time. And it's creates a whole new concept. I mean, it was one of the part in the book I like where he talks about, there are many examples of this kind of thing. But he talks about how even the concept of news of the day, it didn't exist unless you had a medium that you could see what was going on in faraway places, and made me think that that's one of the other things about Twitter.

Here's the line I like. He says the news of the day is a figment of our technological imagination. And if one thinks about not just Twitter but any kind of social media or the internet generally is you can instantly see what's going on all the way across the world. And everyone right away have an opinion. I mean, it's like ... So even in Russia, Ukraine, how many times you see people that put little Ukraine flags on their Twitter page? Or how many people, they ... It becomes a show in itself.

How much is this is really genuine and how much of it is just, "Look at me, I'm on what they call virtue signaling. Look at me, I'm on the right side." And you aren't doing crap for Russia, Ukraine, putting a little flag on your profile. You know, you want to do something to help out? There's lots of ways you can help. Rather than just, look at me pandering to the public opinion. So I don't know. Postman makes you ... When you read Postman, you can get pessimistic about this stuff.

Joel Bowman:

Right.

Chris Mayer:

He knows it too because he's always critiquing and he doesn't necessarily have solutions. He tries hard at the end of the book to have some solutions to this.

Joel Bowman:

One of the things that I liked, which seems to go a little bit begging nowadays when you've read how-to books or nonfiction type 12 steps to this or what have you. They're heavy on prescribed solutions but not necessarily on asking questions. And one of the things I think that Postman did, at least in one of the interviews that I saw, the interviewer tasked him with like, "Okay, well, you seem to diagnose a pretty good problem here, but what have you got?"

And he came up with a series of questions and I thought it was very Socratic of him where he sat back and said, "Well, I think for a start, we need to be sensitive to the kinds of questions that these new technologies ask of us." For example, who benefits from this particular medium, this new medium of communication, for example? Is it the community? Is it society as a whole? Is it a small group of people who are, excuse me, who are the owners? What problem does this technology solve is another question that he had, and he used the example where he had just been to buy, this will date the interview a little bit, but a brand new Honda Accord when he bought it at 295 and he said the salesperson there at the car yard was upselling him to cruise control.

Chris Mayer:

I remember this interview, yeah.

Joel Bowman:

So what problem does cruise control address? And the salesman was like, "I've never had that asked to me before, but I guess the problem is just keeping your foot on the gas." Of course, Postman's response was, "Well, I've been driving for, whatever, 45 years used now and that hasn't presented itself as a problem thus far." So anyway, just the framework of asking questions-

Chris Mayer:

Yes, that's one of the very memorable bits. I remember that interview because I remember that exact example. And I often think about that. When I get a new technology, oh, what solutions does this solve exactly? What problem does it solve? And it's like you almost read the book because the way he ends Amusing Ourselves to Death is with a whole series of questions. Again, because he's ... But he says there's a good reason for that in the end.

Chris Mayer:

I like this line where he says, "To ask the question is to break the spell." So you get hypnotized by this new medium or new technologies. But if you just ask the question, immediately, you are less under that influence and at least you're thinking about different ways it's impacting yourself and what you can say, what other people are saying, why they're saying it, things like who benefits. There's a lot of questions you can ask. And it diffuses it a little, its influence. Same thing if you see a persuasive piece of advertising, you know what's going on.

Joel Bowman:

Right.

Chris Mayer:

If buying doesn’t make you sell, I want you to buy something. Just knowing that helps break the spell a little bit, right? Not always because sometimes things are so subconsciously influential. You can't really do anything about it. I've noticed that at least with myself sometimes, too. Damn it, they planted this idea in your head. Almost like I want to not see certain advertising. So I don't even want to see it because it's like magic and it pushes little buttons in your subconscious. So, yeah, that's your best route of resistance is to ask the questions.

Joel Bowman:

Yeah, it's a so what do you think of the emperor's new clothes type of question.

Chris Mayer:

Yeah.

Joel Bowman:

Well, actually, now that you've mentioned it, he does look a little naked over there.

Chris Mayer:

Yeah, it is. Postman's books are really easy to read. And this book is like, is it 200 pages long, it's 160 pages. And all of his books are like that. They're short. They're like sub 200. And they're very easy to read, quotable, witty. And they're only dated by the examples, like you said. He'll make references of things going on in Nicaragua or President Reagan. But if you didn't have those examples, it's really applicable.

And he is a really good translator for Marshall McLuhan because he was really influenced by McLuhan. And McLuhan stuff is much more difficult and harder to read. I mean, I have this one here at Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media, which is a classic. I mean, this book came out, I think, in the '60s. But a lot of the ideas Postman has come out of McLuhan. And this book is big, fat book and a dense book. But if you wanted to go into where this stuff came from, you could go to McLuhan.

And there's one part in here, for example, because Postman is big on this too, like I mentioned, he's big into the medium and thinking about, "Well, what its effects are," really what its purpose is, the old Greek word like teleology. It has an almost inbuilt purpose, even though you may not know it. And McLuhan has this one chapter, where he talks about how we're all asleep and we don't necessarily think about what we're saying. For example, he's responding to a general says that, "We're too prone to make technological instruments the scapegoats for the sins of those who wield them."

And Marshall McLuhan is saying, "That's ridiculous." And at first, I remember when I read that quote, I was like, "Makes sense to me," right? Technology, it's how people use it. And McLuhan is saying, "No, that's ridiculous." He goes, "Let me consider this. Suppose we were to say apple pie in itself is neither good or bad, it's the way it's used that determines its value. Or the smallpox virus isn't itself neither good or bad, it's the way it's used that determines its value. Or again, firearms are in themselves neither good or bad, it's the way they're used that determines its value. That is, if the slugs reached the right people, firearms are good.

If TV too fires the right ammunition at the right people, it is good. I am not being perverse," he says. So I love that style because it makes you think, it makes you think about stuff. That's why it's such a great book.

Joel Bowman:

He goes all the way back to the agrarian revolution and the advent of the written word. And then all the way through to ... I guess Postman was probably influenced by his idea of the reading public, for example.

Chris Mayer:

Yeah. The trivium, McLuhan's big on that, the basic building blocks of knowledge. Yeah. And he was a big fan of James Joyce. And, yeah, the ancient Greeks. Yeah, he's challenging to read. But I think ... It took me two months to get to that book and I would just read a little bit every day. But lots of thoughtful stuff in there.

Joel Bowman:

That's interesting. It brings up another point as well. And as a card-carrying Joyce Head, who's about to head off to Dublin for the centennial balloons day celebration this June 16th. Yeah. Write me if you're going to be there and we'll grab a beer with the other freaks and geeks doing the balloon walk is this idea of attention span. And you mentioned this McLuhan's dense and rewarding book if you can put a couple of months into it. And obviously, Ulysses is notoriously a century on. And we're still unpacking all the different layers there.

I'm wondering, to go back to Postman's questioning the nature of the medium itself as opposed to just the information that it's delivering, how you think these new mediums have affected both the individual and society in general's attention span. And how much we can pay attention to ... I mean, we have a look at these news cycles, they seem to just be getting increasingly shorter, where you need to, as you say, have an opinion on the history of Eastern European geopolitics. One week, you need to be a vaccinologist. The next week, you need to be a critical race theorist. The next week, you need to know all these things.

I mean, how are these new mediums affecting our ability to be modern polymaths?

Chris Mayer:

Yes. Yeah, I agree. I mean, society in general, we become very impatient people with what we read. I mean, there's that little acronym people throw around, TLDR, too long, didn't read.

Joel Bowman:

Oh, right.

Chris Mayer:

And that's sad to me. People put that out. Yeah. And they put it out there like they're smart or being witty somehow but summarizing some longer argument in a soundbite. But, yeah, I mean, that's exactly right. A lot of the books in my library, you're not going to find the quick New York Times bestseller. A lot of these books, they take time to get through, but that's the rewarding part of it is to spend a couple of months with one book, an author, an idea and going through it.

I mean, it seems like that's really becoming something that fewer and fewer people are interested in, right? I mean, like you say, it's a death of long-form journalism is another area where you see that. Everything has to be compressed and served up so somebody can get it in 30 seconds of lesson and be done.

Joel Bowman:

Yeah, even I think about this with regards to just the realm of fiction in general. Maybe have a different experience here but pretty much all ... And this seems to go very along that, this would be incredibly unpopular to say, but it seems to go very much along gender lines, where guys tend to read, older guys that I know, tend to read nonfiction and completely issued fiction have just zero patience for it, fall asleep at page three. And it seems to be only women, at least that I speak to, who have any patience for fiction and maybe that's just they have different types of patience or different types of tolerance levels, do you find that as well. It's kind of a weird observation.

Chris Mayer:

Yeah. I mean, one of the things I've observed too is that a lot of new books that come out, especially, I don't know, they're more topical or about investing and they're mostly nonfiction, they all tend to be around 200 pages. Almost like the publishers have drawn a line.

Joel Bowman:

This is the public's attention span!

Chris Mayer:

Yeah, it's 200 pages, substantial enough where you can still sell it as a book between 200 covers, but it's not going to put off anybody to show them this. Every once in a while, there are exceptions, right? And they become noteworthy in themselves. I remember when David Foster Wallace had Infinite Jest. Remember, that was a brick.

Joel Bowman:

Yeah.

Chris Mayer:

And David Graeber's Debt book was another big fat one that became a bestseller. So there are exceptions, but in general, a lot of these books are pretty thin.

Joel Bowman:

I wonder how many of those big classic tomes, if Dostoevsky or Thomas Mann rocked up with Buddenbrooks to the publisher with like-

Chris Mayer:

And then it comes in with Critique of Pure Reason, here you go.

Joel Bowman:

I'm sorry, you've got to ... Yeah, you're going to have to-

Chris Mayer:

We'll break that up in a series of 10.

Joel Bowman:

Yeah, yeah. How about we do a Netflix special and then people can binge it overnight? So do you-

Chris Mayer:

There's one thing you mentioned that I want to get to before I forget was you said about, you have to feel like you have an opinion about everything. In one week, you're a vaccinologist. And next week, you're an expert on recurring foreign pot. I mean, that's classic.

But that reminded me of one of Postman's solutions. And it's not in any of the books we've discussed. There's another book called How to Watch the News or something like that. But in the end, he gives 10 things. And one of them is, try to reduce the number of opinions you have by a third. So it's just an interesting exercise to go through. Try it yourself just for a week. Try to ... Instead of when you see some story or some idea, try not to have an opinion about it and say, "I don't know."

Joel Bowman:

Yeah.

Chris Mayer:

It's interesting. It's almost a little liberating because every time you take an opinion, it's almost like you're staking some ground and making a commitment because then people are more reluctant to change their opinions. So if you try to withhold your opinion as long as possible and limit the number of opinions you have, it's interesting psychological effect, just trying it out.

Joel Bowman:

I could see how that could have a cascading effect as well in an increasingly bifurcated society, where if you voice a particular opinion on one issue, it almost hems you in with regards to a whole litany of other issues that might have absolutely nothing to do with the original issue at hand. I mean ...

Chris Mayer:

Absolutely.

Joel Bowman:

... things that are completely independent like, "Oh, you believe in global warming, okay, you have to wear masks during a pandemic outside playing golf." Just things that have nothing to do with one another, but we have to be Team Red or Team Blue.

Chris Mayer:

Yeah, exactly. What, do you believe in climate warming? Well, Trump was a good president. What do you mean? How are those two related?

Joel Bowman:

Right.

Chris Mayer:

Everything's politicized or whatever. That's another reason why they resist labels. That's another exercise is just resist labeling yourself, resist taking on any label because, again, that hems you in. Suddenly, you think yourself as a X. And there's some internal pressure to believe everything that an X believes or whatever. And it makes you take sides just based on a label rather than reasoning your way through the issues.

Joel Bowman:

So do you think that there's a takeaway or some applicable lesson to be drawn as an investor? I mean, in definitely multiple senses, if you're the one guy who's going to sit through and read the big dense tomes and not just skim the executive summary, does that give you an edge, or?

Chris Mayer:

Yeah, I think there's always an edge for the patient, who are willing to read the footnotes, as the old saying goes. But it's tough because if everyone else thinks the other way, in the short term, you can look pretty dumb. And you can look pretty dumb for a while. I mean, it could go on for months or you may not get validation for a year or several years.

So it requires patience to go through that but also patience to then suffer when things aren't going your way for a while. I see it all the time. Some report will come out on some company and I'll know that it's sensationalist and not particularly true in certain areas, but it'll still not stock down from 10% or 15%. And then it may not recover for months until it cycles through. And for those of us who are professional investors and live on reported returns, it can be difficult. Well, just hang on, it's coming.

Joel Bowman:

Right. I guess it must happen the other way, too. Yeah, go on.

Chris Mayer:

Yeah. Otherwise helps too, I was talking about labels. I mean, people will label certain companies in certain ways because they want you to think about it in a certain way. But you get past the label. So for example, I don't know, let's take a random example, people that are being on Tesla will want you to think of Tesla as a technology company in some way or is a battery company, where people who are not so enamored with Tesla folks and say, "Well, no, it's a car company." And they look at it through that lens.

And so you come through very different points of view, depending on what label you adapt. And that happens all the time as well.

Joel Bowman:

And I guess it must go the other way as well when something flashes across the news and new technology and something shoots to the moon. And you might be sitting there saying, "Actually, this thing, it doesn't have any earnings. It's got no growth. It's got no pathway to profitability." But you're watching a mania unfold.

Chris Mayer:

That's probably actually more common because I've been in volatile markets close to 30 years and I've seen that happen many times to me, where I'll be sitting and these companies will be flying and I won't be involved in any of them, but it takes time and then they unravel. So you see companies like Carvana didn't make any money but has a concept that got people excited and went to the moon. And now it's starting to finally come apart. There's a lot of other businesses like that that don't make any money. But they had a concept.

And what I've seen people do, and particularly younger investors will do, I mean younger than me, they'll focus on things that I thought they'll talk about unit economics. So they'll say, I don't know, I don't want to use too many specific name companies, but let's say Company X, they sell something. And the unit economics of what they sell is really compelling. But the company overall is still not making any money because the operating expenses and everything below that line is high and it continues to grow. But they say, "Oh, when it scales." And then they do these projections based on unit economics.

And what happens a lot is those businesses never get to that scale or they continue to grow, but the operating expenses continue to grow right along with it, and they never quite get there. And so I have this basic rule that I want companies to make a GAAP profit, a profit according to generally accepted accounting principles. And if you just have that filter alone, I know you would have avoided a lot of the trouble over the last six to nine months, where these companies have fallen 70%, 80%, 90%. Didn't make any money, but for a little while, they were darlings.

Joel Bowman:

Yeah, it's interesting. I spoke to our mutual friend, Mr. Eric Fry, last week. And I asked him if there was a couple of key takeaways that he could give to our listeners with regards to investing and when you're getting all this noise to talk again about the Postman idea of this saturation, this glut of information, how to cut through that noise in just a couple of basic starting filters that investors can use.

And he said at the margin, you can cut out a lot of noise by just looking at earnings as a company outgrowing earnings. And he said, "It sounds almost facile, but it's ignored by a lot of people because they focus on crafty accounting." And Eric referred to it as accounting wizardry where, well, it's earnings but it's adjusted for this, or all these other adjustments that the accounting department makes that can hide a lot of a company's lack of earnings or lack of earnings growth.

And then one of your favorite indicators, of course, was insider buying or selling. And at the margin, you're not going to be right all the time but those two things can help cut out a lot of the information or the glut of information that is maybe not as worthwhile as others would have one believe.

Chris Mayer:

Yeah, I would say overwhelmingly, for most investors probably, almost everyone is listening to us, just following the companies that make a profit. Just that filter alone. Now, we have to be fair, you're going to miss sometimes a great business. I mean, Amazon didn't report a GAAP profit for quite a while, right? So you're going to have to ... I wrote a blog post about this not too long ago, that every filter you create is going to have fish slipped through the net. I mean, that's the nature of it, you're not going to catch everything.

But the idea of having a filter as an investor is to cut down on that universe because if you're looking globally, as I do, there's tens, thousands security. So you have to find some way to look at that world. And for me, yeah, profit. The other way to do it is inside ownership that cuts out a lot of stuff. I'm only investing in companies where there's a family or there's a CEO or somebody owns a decent slug of stock.

The other thing that you always use is balance sheet, just looking at anything that's got a lot of debt out. So if you just sift by that, suddenly, the stuff that falls through is worth taking a look at, usually. And doesn't mean, of course, that there isn't some debt-fueled company that has no insider ownership that's going to be a 10 bagger. Of course, I'm going to miss that.

Joel Bowman:

Right.

Chris Mayer:

But that's the nature of filters.

Joel Bowman:

And I guess it imposes whether you're looking at information just in general from the media. It could be political information or entertainment information or whatever the news cycle is, or information that informs your investing. If you employ some of these tools, then it can impose a lot of self-discipline on you, when you're just focused on a smaller universe, as you say.

Chris Mayer:

It does. And then the other question, I take a very hard pragmatic approach when it comes to trying to sift through news and economic reports is I always ask myself, "Well, what would be the consequence of taking a belief here either way? Would it matter?"

Joel Bowman:

Taking a kind of agnostic approach from the outset, yeah.

Chris Mayer:

Yeah. Yeah. I mean, it was a mix ... Should I spent a lot of time figuring out the Russia-Ukraine thing? What practical difference would it make to me to take one side or the other? Or just lots of political questions or that way. And it helps you conserve your mental energy and your focus.

Chris Mayer:

There's another saying I like, where it's ... I don't know who first said it, but it's you are what you pay attention to. So you think about that, you are what you pay attention to. So if you pay attention a lot of this trivial nonsense all the time, that's who you are, that's who you become. Do you want to be that? Feed your mind good stuff. Pay attention to things that have some consequence that matter.

Joel Bowman:

Yeah. I think virtue is the habits that we undertake every day.

Chris Mayer:

Yeah.

Joel Bowman:

And it can be a bit of a spiral. I mean, I think we've probably, all listeners included, been around people who are so caught up in the whirlwind of Postman's information glut and this rapidly constricting news cycle that it's pretty easy to get yourself overheated. I mean, just from like a mental health standpoint, it's pretty easy to get yourself overheated on things that, well, are you going to become an expert in this in the next day or weeks? Shouldn't you focus on things that are, that old Voltaire quote, of tending your own garden that we have other things to do.

Chris Mayer:

There's a lot of wisdom like that. Girth is about sweeping your own doorstep.

Joel Bowman:

Sweeping your own doorstep, yeah. There you go.

Chris Mayer:

Wise people. But it gets to the title of his book, Amusing Ourselves to Death. So much of this is really entertainment. I mean, what we call news is entertainment. It's packaged that way. It's meant to elicit a reaction. And if you allow yourself, you're just letting them tug in control of you. So, yeah, I think that's a good message out of that.

Joel Bowman:

And so just changing tack slightly, what do you think of Twitter as a tool? I mean, we've talked about the drawbacks and the potential detrimental effects. I know a lot of people who see it as a tool to be able to cut through other information because they're able to focus on maybe a few investors that they like, and they follow, and it's kind of real-time.

Chris Mayer:

Yeah, I have a love and hate relationship with Twitter, really, because on the one hand, I've met some interesting people through Twitter. That has been valuable. There's been research that has been exchanged over Twitter. That's been valuable. I've got, I don't know, over 30,000 followers. So from a business perspective, it brings attention. I know at least a couple of investors have found me through Twitter. So it's not of no value, but then I am very mindful of the downside, too. So there are ways that I manage it. I'm only on it for certain times. So I'll go and try and tweak some things.

I like to joke with my friends and say, "My Twitter account is a one-way feed." I put stuff out but I'm not going to engage anybody. Don't be offended if I don't see your tweet, I don't favorite you and retweet you. I don't do it for anybody. I don't pay favorite and tweet. I have lots of people I follow. It seems almost like a courtesy and they follow you. "Okay, I'll follow you." But I don't get into it that much because it's an enormous time sink otherwise.

And you find yourself just ... I've had this early on when I was on Twitter, you're there for 45 minutes and then you're done. You're like, "Well, what did I do?" It's like junk food for the brain. What did I really get out of it? Yeah. So I tried to manage it. I limit myself.

And the other things I've learned too, and this was earlier on, I used to talk much more about positions. But then I found that was a negative to do that because then people start to think of you as the guy for that position and then they want to come and ask you everything, every twist and turn. You got to be the guy who narrates it for people. And again, it may affect me in ways I don't really appreciate, forced me to dig in on a name that otherwise if all these people didn't know I owned it, they'd be gone or whatever.

So I've limited that as well. I have discussed some names, times, but I don't give people the running commentary of what I'm doing or any of that anymore. So there are ways to manage it. Yeah.

Joel Bowman:

If they want the running commentary of what you're doing, they can follow your blog and I'll give you a plug, Chris, at woodlockhousefamilycapital.com for our listeners who want to find out more about your work.

Chris Mayer:

There you go. Thank you. You Google that and you'll find it. I write an occasional blog and then my Twitter which I do occasionally. The other annoying thing about Twitter is I keep getting these impostor accounts.

Joel Bowman:

Oh, really?

Chris Mayer:

It's crazy.

Joel Bowman:

Do you have the real Chris Mayer or something like that? What's your handle so people can avoid those?

Chris Mayer:

No, I tried Twitter. I tried to get verified a couple of times and they keep rejecting me. I think I'm just not quite famous enough or something.

Joel Bowman:

Oh, okay.

Chris Mayer:

But it's terrible because people will come up with a Twitter page, it looks exactly like mine. My handle is chriswmayer. They'll change it by some minor way. It'd be chrisi or they have two i's in or an x or something like that. But they make the page otherwise look exactly like mine and they tweet the same thing. And then they use it to sell some garbage.

Most of the time, I've caught them pretty early and they don't have very many followers. But there was one that I just found, people were telling me about, has more followers than my real account. It's pretty embarrassing.

Joel Bowman:

Wow. Well, maybe you'll get the Fatal Conceits podcast bump and that will get you up to blue check status.

Chris Mayer:

There you go. That's it. I need that blue checkmark. I mean, there are other investors I know, they have blue checkmarks. And they're not particularly any more famous than I am. I mean, within investing, they're known, but they're not really that well known outside that world and they have blue checkmark. So I don't know what they did.

Joel Bowman:

Well, we'll probably have a whole other discussion on just the elitism that goes on within the new communication technology platforms. But one, you're talking about Twitter being a one-way relationship for you then and it reminded me of one quote of Postman's, which I wanted to get in. And this is another one of the questions that he routinely asks in order to frame the discussion you see. It's constantly going on in his own head. And it's as simple as, am I using this technology or is it using me? I think that cuts to the heart of the matter.

Chris Mayer:

I like that one. That's really good. That's really, really good.

Joel Bowman:

Right.

Chris Mayer:

Yeah. Yeah, the irony is I'll put that on Twitter.

Joel Bowman:

But in a one-way relationship.

Chris Mayer:

There you go.

Joel Bowman:

All right, Chris, that's probably a pretty good place to leave it for this one, mate. Thank you as always for sharing your insights. You've recommended so many good books to me over the years...

Chris Mayer:

Well, that's good. I'm glad you like Postman and, clearly, you've read quite a bit of stuff because you were spot on the whole time. Yeah.

Joel Bowman:

I'll put a link to a few of his books underneath because hopefully our listeners can get something out of them as well.

Chris Mayer:

And another one, Technopoly, I think it is. Those are the two that I would really recommend. Very good. And then after that, you can find your way to his other books as you're interested in different topics.

[Ed. Note: Find these two books here…

Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business

Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology

Joel Bowman:

Perfect. Chris Mayer, Woodlock House Family Capital fund, check it out. And chriswmayer, don't be taken in by the impostors on Twitter. And for our listeners, please head over to our Substack, which is at bonnerprivateresearch.substack.com, where you can find plenty more material, including conversations just like this one. That's all. Catch you next week.

Share this post